Dragonflies and fireflies are some of the most well-known insects in the United States. Dragonflies are easily recognized by many people thanks to their large size, bright colors, and incredible flying abilities, while fireflies are famous for the surreal light shows they put on over meadows and in woodlands across the eastern United States. But despite sharing many basic characteristics which makes them “insects”, they are far more different from each other than similar.

Dragonflies and fireflies are both insects but differ in size, anatomy, behavior, life cycle, habitat, means of defense against predators, and number of known species. Dragonflies are classified in order Odonata, suborder Anisoptera. Fireflies are beetles in order Coleoptera, family Lampyridae.

Both dragonflies and fireflies are fascinating creatures that can add a lot to your enjoyment of the natural world. And with approximately 336 dragonfly species (Paulson 2014) and 81 firefly species within 13 genera (Evans 2014) known in eastern United States and Canada, learning more about them is definitely worthwhile. Read on to discover the differences between these two kinds of insects.

Dragonflies rely on water; fireflies live on land

Both dragonflies and fireflies hatch from eggs as immature forms of the adults they will eventually become but inhabit different environments.

Dragonfly eggs hatch underwater and the immature insects, known as “naiads”, spend many months living on the bottom of lakes, ponds, streams, and rivers. Naiads are well-suited to their aquatic habitats. They absorb oxygen from the water through special gills located in their abdomens and either crawl along the substrate using their six legs or propel themselves forward by expelling water from their abdomens under great pressure.

All dragonfly naiads are predators and actively hunt aquatic invertebrates, tadpoles, small fish, and even their fellow dragonflies. They shoot a specially modified part of their mouths called the “labrum” forward from their heads at speeds too fast for their prey to react and evade. Once their labrums have captured the targeted prey, the naiads retract them and chew the prey to death with their strong mandibles.

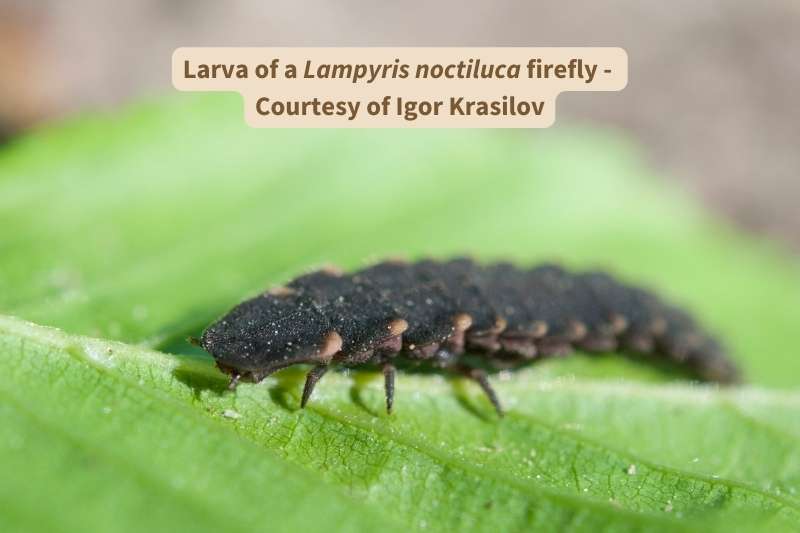

In contrast, firefly larvae are entirely terrestrial; their eggs hatch underground and the larvae emerge to grow and develop on dry land. Also predators, firefly larvae actively hunt snails, slugs, earthworms, and also attack their fellow fireflies, usually under leaf litter or in vegetation low to the ground.

Like dragonfly naiads, firefly larvae have six, jointed legs with which they crawl around and have strong, sharp mandibles with which they attack their prey. However, they lack extendable labrums and do not kill their prey by biting it apart. Instead, firefly larvae paralyze, kill, and liquefy the tissues of their prey thanks to special biochemicals that flow into the prey down special channels in their mandibles (Evans, 2014).

Dragonflies and fireflies use different defenses

Despite being voracious and powerful predators for their size, dragonfly naiads are preyed upon by a variety of bigger, stronger aquatic predators, such as large fish, frogs, and larger dragonfly naiads and conceal themselves under debris when not actively hunting. If attacked, naiads can bite using their sharp mouthparts or shoot out of reach by squirting water out of their abdomens under high pressure. These defense strategies may or may not work and are entirely physical in nature.

In contrast, many species of firefly larvae can sicken or kill predators if eaten, thanks to a toxin they produce and store in their body tissues called “lucibufagin” (Berger et al 2021). Not every firefly species can manufacture this chemical; those that lack this ability obtain them second-hand by eating their cousin species that can.

Fireflies advertise this defensive capability using their most famous ability – bioluminescence. All forms at every life stage has the ability to generate light using two special chemicals called “luciferin” and “luciferase”. Fireflies mix these two enzymes together at will and the combination creates visible light. In the case of firefly larvae, this light serves as a visual warning to potential predators that the insects are dangerous – a strategy known as “aposematic communication”.

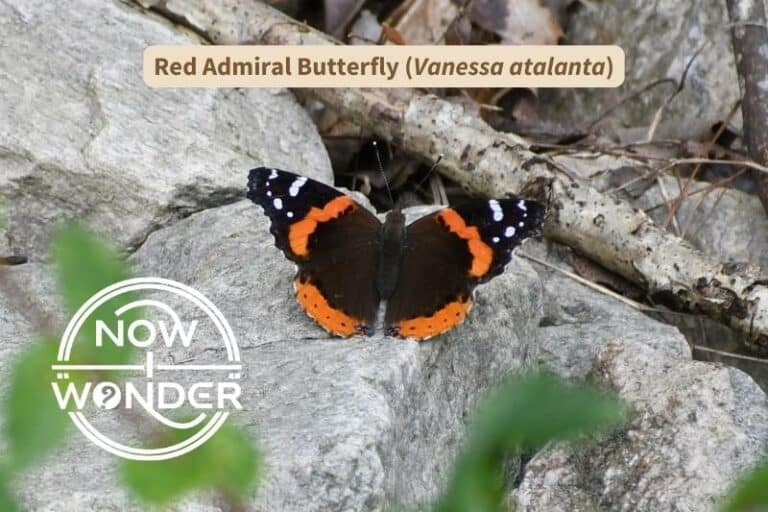

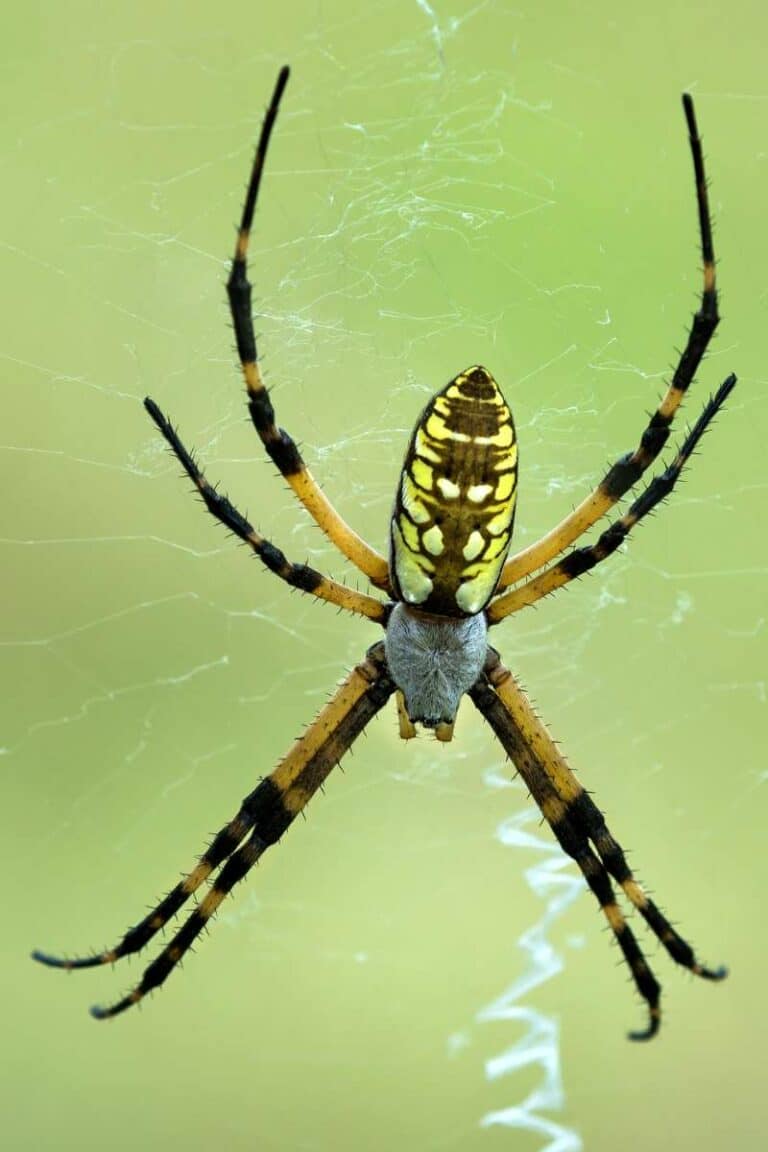

Unfortunately, the visual light warnings and toxic body tissues are insufficient to prevent all predatory attacks. Fireflies are still vulnerable to predators such as orb-weaving spiders (Araneidae) and harvestmen (Phalangiidae) (Faust, 2010).

To learn more about aposematic communication in other animals, check out these other Now I Wonder posts “What makes ladybugs and Japanese beetles different?” and “What do grasshoppers do? A day in their lives“.

Dragonflies and fireflies metamorphose differently

Another major difference between dragonflies and fireflies relates to how they transition from their immature forms into their mature, adult forms.

Dragonflies undergo incomplete metamorphosis (also known as “hemimetabolism” or “partial metamorphosis”). This means that the immature naiads are visually similar to the adult forms, with the important exceptions of body coloration, the presence of wings, and body size.

Naiads are usually brown to match the substrates of their underwater habitats, and do not develop full wings until they emerge as full adults, although wing buds develop during the aquatic life stage. Additionally, naiads are much smaller than adults. They grow larger in stages called “instars”, which culminate when the fully developed naiads crawl out of the water, split their exoskeletons down the middle, and pull themselves out of their larval skins.

In contrast, fireflies, like all beetles, undergo complete metamorphosis (also known as “holometabolism” or “full metamorphosis”). This means that the larvae look completely different from the adult form. In fact, the only characteristic that larvae and adults share is the presence of six, jointed legs. Firefly larvae are multi-segmented creatures, looking more like armored caterpillars than beetles. Insects that undergo complete metamorphosis have an extra pupal stage in their life cycle. It is during this stage that the firefly larvae’s tissues completed rearrange themselves into their adult forms, including growing wings from scratch.

Dragonflies and fireflies have different adult forms

Dragonflies are relatively long-lived insects, living for several months in the southeastern United States between late spring and early fall, depending on the species. All adults are carnivorous, without exception. They spend much of their time in flight, hunting a wide variety of flying insects, which they capture in mid-air, locating suitable mates, and mating.

These are large, conspicuous, day-active (or “diurnal”) insects. Physically, the largest adult dragonfly species in the southeast reach up to 3.5 inches (9 cm) in total body length. Dragonflies have extremely large eyes composed of thousands of individual lens which meet in the middle of their heads, more mobility between their heads and thoraxes than most insects, and large, strong chewing jaws. This combination gives dragonflies extraordinarily acute vision for color, movement, and polarized light, a very wide visual field, and the power needed to dismantle their insect prey easily.

Dragonflies also have a unique body shape and hard, protective exoskeletons. Their segmented abdomens are long and thin, while their thoraxes are bulky and house the large wing muscles that power their strong, acrobatic flight. Dragonflies have two pairs of long, narrow wings that extend perpendicularly from the thorax and are held out to the side at rest – never folded over their bodies – which gives them a distinct silhouette.

Dragonflies are famously fast and agile fliers, able to obtain straight-line speeds of up to 35 mph (56 km/hr), reverse direction within one body length, hover, and fly backwards and upside down with ease (Imes 1992). This skill serves them well to chase down flying insects for food and flee predators.

In contrast, adult fireflies are much smaller insects, usually 0.2 – 0.8 inches (5 – 20 mm). Their bodies are softer than those of dragonflies; their exoskeletons are more leathery than hard. The first segment of their thoracic exoskeletons, which is called the “pronotum” (Collins Dictionary of Biology, 2nd ed., 2005, s.v. “pronotum”), evolved into a hood that covers the dorsal side of their heads. Fireflies have good vision but their extended pronotums limit their field of view. Their abdomens are much shorter than those of dragonflies, and contain their famous light-producing organs.

Many firefly species fly well, but the females of some species, such as females in genus Photinus, fly weakly or not at all. As beetles, fireflies have only one pair of flight wings, which are membranous and folded carefully away on top of their abdomens when at rest. These hind wings are protected by wing covers called “elytra” which are modified fore wings and serve as airfoils to stabilize and steer the insects’ flight. These leathery wing coverings meet down the middle of the fireflies’ backs and are characteristic of beetles in order Coleoptera.

Rather than rely on flight speed and agility, fireflies rely on their defensive steroid lucibufagin to deter predators. Many species exude this toxic chemical onto their bodies through special weak points in their exoskeletons, especially at leg joints, to make themselves unpalatable or sicken predators that eat them. This defense mechanism is known as “reflex bleeding” and is one that fireflies share with other beetle species, such as ladybugs (family Coccinellidae).

Species that fly well are active at dusk and at night, when the light they produce is most visible, and hide from predators during the day. Flightless species, or those that don’t bioluminesce, such as those in genera Ellychnia, Lucidota, and Pyropyga, are more active during the day and can be found in vegetation (Evans 2014).

Dragonflies and fireflies locate mates differently

Dragonflies live their adult lives within flying distance of ponds, lakes, rivers, and streams as they must lay their fertilized eggs in water. Their bodies are usually brightly colored, which is important for species recognition, as they rely on their acute vision to identify members of the opposite sex but the same species from a distance. Males will fly in pursuit of females, clasp them firmly around the head with their abdominal claspers, and transfer spermatophores to the females to fertilize their eggs, all while in flight. The females then fly over water and lay their eggs by dipping their ovipositors under the surface, often while either being guarded closely by their mates or even still physically connected to them.

In contrast, fireflies mate on the ground or in vegetation, rather than in flight, and while they rely on vision to locate mates, they use a much different method than dragonflies. They search for mates at night when their ability to produce light on command is most useful. Fireflies are drably colored and mostly brown or black but every firefly species bioluminesces in a particular color and pattern unique to that species.

Males and female fireflies arrange themselves at different levels within their woodland or meadow habitats; males fly several feet above the ground vegetation, where females perch. The males flash their abdomens and search the vegetation below them for an answering light signal created by the females. The males zero in on the answering flashes and fly into the vegetation to encounter the females.

Most of the time, this mate location strategy works well; a male of one species intercepts a female of the same species, thanks to their coordinated, species-specific flash pattern, and the two mate. But some species of predatory fireflies evolved the ability to mimic the flash pattern of others. Most adult fireflies do not feed, except for the females of several species of Photuris, which eat males of other firefly species (Maquitico et al 2022). For example, Pennsylvania fireflies (Photuris pennsyvlanicus) mimic the flash pattern of Big Dipper fireflies (Photinus pyralis). The predatory females lie in wait in vegetation, flash the trick signal at the overhead males to tempt them dangerously close, then attack the hapless pyralis males who wing in expecting to find a female of their species. This is an excellent survival strategy for the photurid females; they cannot manufacture their own defensive biochemicals but obtain both nourishment and the pyralis’ lucibufagin by eating the tricked male fireflies.

Related Now I Wonder Posts

For more about beetles in order Coleoptera, check out these other Now I Wonder posts:

- What makes ladybugs and Japanese beetles different?

- What eats Japanese beetles?

- June Bugs vs. Japanese Beetles: What’s the difference?

- What is the biggest beetle in North Carolina?

For more about dragonflies and other insects in order Odonata, check out these other Now I Wonder posts:

- Is a dragonfly a fly?

- Can dragonflies walk?

- What do dragonflies do at night?

- What is the difference between a dragonfly and a damselfly?

- Dragonflies vs. Butterflies Part 1: First Comes Form

- Dragonflies vs. Butterflies Part 2: Second Comes Function

- Are there different types of dragonflies?

- Dragonflies vs. Horse Flies: Allies vs. Enemies

- What is the difference between dragonflies and mayflies?

- Dragonflies vs. Mosquito Hawks: What’s the difference?

References

Berger, Andreas, Georg Petschenka, Thomas Degenkolb, Michael Geisthardt, and Andreas Vilcinskas. 2021. “Insect Collections as an Untapped Source of Bioactive Compounds—Fireflies (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) and Cardiotonic Steroids as a Proof of Concept.” Insects 12 (8): 689. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/insects12080689.

Evans, Arthur V.. 2014. Beetles of Eastern North America. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Faust, Lynn Frierson. 2010. Natural History and Flash Repertoire of the Synchronous Firefly Photinus Carolina (Coleoptera: Lamyridae) in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The Florida Entomologist 93 (2) (06): 208-217

Imes, Rick. 1992. The Practical Entomologist, New York (NY): Quarto Publishing plc.

Maquitico, Yara, Aldair Vergara, Ilana Villanueva, Jaime Camacho, and Carlos Cordero. 2022. “Photuris Lugubris Female Fireflies Hunt Males of the Synchronous Firefly Photinus Palaciosi (Coleoptera: Lampyridae).” Insects 13 (10): 915. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13100915.

Paulson, Dennis. 2012. Dragonflies and Damselflies of the East. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

“pronotum.” In Collins Dictionary of Biology, by W. G. Hale, Venetia A. Saunders, and J. P. Margham. 2nd ed. Collins, 2005.