What is that thing that comes out of an anole’s neck?

Like many lizards, green anoles can expand the flexible skin beneath their lower jaw and neck into a large pink bulb called a “dewlap”. While both sexes have dewlaps, males extend them more often than females, usually as visual displays to intimidate rivals and advertise their physical condition.

Also known as a “throat fan”, the dewlap is made of skin that is more elastic than the skin covering the rest of the lizard’s body. This elasticity allows an anole lizard to extend the skin into a large, rounded bulb when desired.

The size to which a dewlap can extend is related to the size of the individual lizard, the sex of the individual and how often an individual anole uses it. Larger dewlaps are seen on males, in larger individuals, and in those anoles who expand their dewlaps the most.

Both males and females have dewlaps and both sexes extend their dewlaps when defending territory and advertising to members of the opposite sex. But male dewlaps are approximately three times the size of female dewlaps (Jenssen 2006).

Dewlap elasticity and extended size increase from spring to fall because dewlap extension is an important communication tool for these animals, especially for the males.

Male lizards stretch their dewlaps out over time as they signal other males in territorial and mating fights and as they display for females prior to mating. The maximum extended dewlap size decreases fall through winter because the male anoles aren’t using them as much or as often (Laivaux et al. 2015).

Anoles have excellent eyesight; expanding a dewlap is an effective way of communicating a signal across a distance. A resident male will expand his dewlap to warn an intruding male that he is physically fit and prepared to fight if the intruder encroaches on his territory and females.

Sometimes an intruding male may evaluate the resident male’s dewlap display and decide that encroaching on his territory is worth the risk.

A male anole lizard is much less likely to extend his dewlap to cow a rival when the two are closer together. In a fascinating study by Kristi R. Decourcy and Thomas A. Jenssen, males extended their dewlaps 92% of the time at distances greater than 100 cm but only 7% of the time when they were within 20 cm of each other (Decourcy and Jenssen 1994).

Male to male dewlap extension is a strong visual display, meant to warn a distant intruder to “stay away”. If the intruding male ignores the signal and continues to approach, the resident male tries other tactics, such as gaping his mouth, turning broadside to show off his size and doing “push-ups”.

Why do green anole lizards do push-ups?

When a green anole does “push ups”, it is attempting to either intimidate a rival or show off to members of the opposite sex by bobbing his head. Both sexes demonstrate this behavior but male anoles bob more frequently than females, especially during mating season.

Male anole lizards bob their heads for two reasons and may or may not combine head bobbing with dewlap extension.

The first reason is to advertise themselves to any females in the vicinity who might be watching in the hopes of mating.

The second reason is to intimidate an intruding male who might steal the male’s territory and resident females.

When advertising to females, males bob their heads up to 3 times a minute and usually extend their dewlaps (Decourcy and Jenssen 1994). When signaling to other males, they will bob their heads more as they get closer together. Anoles more than 100cm (39 inches) apart bobbed their heads up to 4 times per minute, while those that were within 20 cm (8 inches) of each other bobbed up to 8 times per minute (Decourcy and Jenssen 1994).

Green anole lizards use three distinct patterns of head bobs, which are categorized as Types A, B, and C (Decourcy and Jenssen 1994). The A Pattern begins with a triple head bob series, the B Pattern begins with a “little/big” bob series and C Pattern begins with a single large bob (Jenssen unknown).

Males work hard to defend both their territories and their females. They put on visual displays much more frequently than females. Males display approximately 100 times per hour compared to only 12 times per hour for females (Jenssen, 2006).

Additionally, a male green anole may change his perch 28 times in an hour and cover more than 27 meters (30 yards) compared to a female who might relocate only 6 times and 4 meters (4.5 yards) during that same hour (Jenssen, 2006).

Unfortunately, time spent patrolling against interlopers, intimidating rivals, and showing off for females is time the male can’t spend hunting food.

Male anole lizards lose body weight during the summer months because their hunting time is reduced just when they need as much energy as they can get. Resident males who successfully defend their territories against rivals at the start of the mating season are often beaten and displaced later in the summer out of sheer exhaustion (Jenssen, 2006).

Do green anole lizards fight each other?

Male green anoles will fight each other over territories, mating rights, and when guarding females within their territories if intimidation attempts fail. Females will fight other females occasionally but they are less territorial than males.

Head bobbing, dewlap extension and mouth gaping all serve to avoid physical confrontations but the right to mate is the ultimate goal and sometimes actual fights between males are inevitable. At that point, both males are at risk for serious, even deadly, injury, regardless of which lizard wins the battle.

Lizards have teeth and can bite hard. Despite their scaled bodies, anoles can be hurt or killed when confrontations turn violent.

An anole lizard may survive the initial fight but succumb to injuries afterwards. Wounds to the skin can cause infection or death by dehydration (Hibbetts and Hibbetts, 2015). Other injury, such as to the toes, tail or eyes, can slow him down, interfere with his ability to climb, and make him much easier prey for a predator.

Therefore, anoles prefer intimidation over actually fighting when possible. Two males will absolutely fight if neither lizard backs down and there will always be a winner and a loser. But in general, they prefer using their dewlaps and head bobs to using their teeth and claws.

Do green anoles lay eggs?

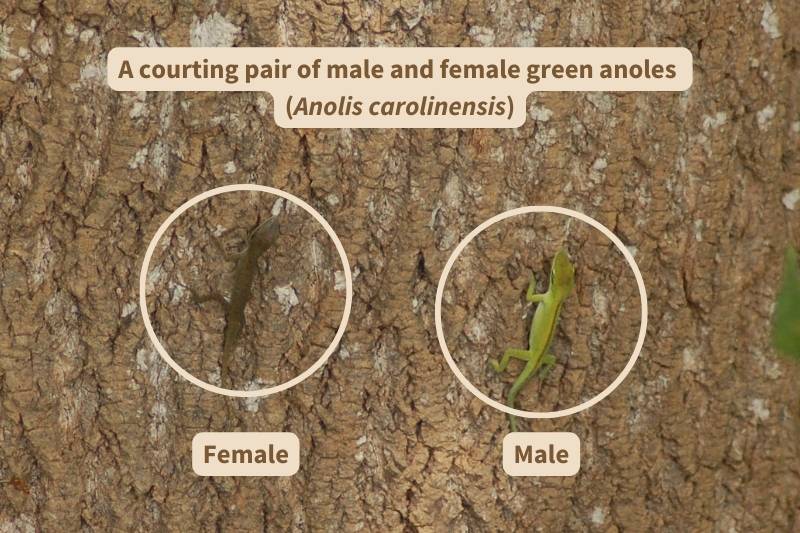

Female green anoles (Anolis carolinensis) lay single eggs in leaf litter and rock piles every 14 days through the mating season of April to September. Incubation takes approximately 5 weeks. Females provide no direct care to the eggs or hatchlings.

Unlike other reptile species that lay clutches of several eggs at once, green anoles lay only one egg at a time. Female green anoles have two ovaries but only one follicle develops at a time; the ovaries take turns producing eggs (Martof et al. 1980). A female has to be courted by a male in order to ovulate; her ovarian development is triggered by the sight of a displaying male (Martof et al. 1980).

Related Now I Wonder Posts

To learn more about lizards, check out these other Now I Wonder posts:

For more information about snails and slugs that some lizards prey upon, check out these other Now I Wonder posts:

- What are slugs?

- What do slugs eat?

- What is the large spotted slug called?

- What is the difference between slugs and snails?

References

Decourcy KR, Jenssen TA. 1994. Structure and use of male territorial headbob signals by the lizard Anolis carolinensis. Animal Behavior. [Abstract]. [Internet]. [cited 2022 June 17]; 47(2): 251-262. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0003347284710372

Hibbitts, Troy D., and Hibbitts, Toby J.. 2015. Texas Lizards : A Field Guide. Austin: University of Texas Press. Accessed June 22, 2022. ProQuest Ebook Central. 333 pages total.

Jenssen TA. Display patterns of male and female Anolis carolinensis. Published date unknown. [Internet]. Blacksburg (VA): Office of Thomas A. Jenssen (Emeritus); [cited 2022 June 17]. Available from: https://www.faculty.biol.vt.edu/jenssen/dispatterns.html

Jenssen TA. The Green Anole (Anolis carolinensis). 2006. [Internet]. Blacksburg (VA): Office of Thomas A. Jenssen (Emeritus) Anolis Behavior; [cited 2022 June 17]. Available from: https://www.faculty.biol.vt.edu/jenssen/

Lailvaux SP, Leifer J, Kircher BK, Johnson MA. 2015. The incredible shrinking dewlap: Signal size, skin elasticity, and mechanical design in the green anole lizard (anolis carolinensis). Ecology and Evolution. [Internet]. [cited 2022 June 17]; 5(19):4400-9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.1690

Martof B, Palmer W, Bailey J, Harrison III J. 1980 Amphibians and reptiles of the Carolinas and Virginia. Chapel Hill (NC): The University of North Carolina Press.