Pipevine Swallowtail butterflies live in forests throughout North Carolina. They have black forewings, and a row of white spots on their hindwings. Male hindwings are bright, metallic blue. Female hindwings are dark, with larger and brighter hindwing spots. They are toxic to many predators.

Fun Facts About Pipevine Swallowtail Butterflies to Wow Your Friends

- Pipevine Swallowtail butterflies are toxic to most predators.

- Most birds learn to avoid attacking this species.

- The caterpillars feed on poisonous plants in the Birthwort family Aristolochiaceae. These plants manufacture aristolochic acid, which is toxic to many animals.

- Consuming the aristochic acid doesn’t hurt the Pipevine Swallowtail caterpillars. Instead, the caterpillars store the toxic chemical in their tissues.

- The toxins remain in their bodies even through their metamorphosis into butterflies.

- The aristolochic acid in Pipevine Swallowtail butterflies makes them taste bad. Actually swallowing one of these butterflies can make a bird sick. So, most birds avoid attacking any butterfly that looks like a Pipevine Swallowtail butterfly.

- Female Pipevine Swallowtails lose some of the toxic chemicals as they age. This is probably because they donate some of the chemicals to their eggs (Fordyce et al. 2015).

- Male Pipevine Swallowtails don’t seem to have this problem. The level of toxic chemicals remain constant in their bodies throughout their adult lives (Fordyce et al. 2015).

- Several North Carolina butterfly species look like Pipevine Swallowtail butterflies but are entirely edible. These include:

- Female Diana Fritillaries (Speyeria diana)

- Dark form female Eastern Tiger Swallowtails (Papilio glaucus)

- Female Black Swallowtails (Papilio polyxenes)

- Female Spicebush Swallowtails (Papilio troilus)

- Red-spotted Purples (Limenitis arthemis astyanax)

- Mimicking a dangerous creature even though you, yourself, are harmless is called “Batesian mimicy”.

- In Batesian mimicry, only the harmless animals benefit. There is no advantage for the dangerous model species.

- Pipevine Swallowtail butterflies might be involved in another example of Batesian mimicry. But this time, they are the mimics of a more dangerous creature.

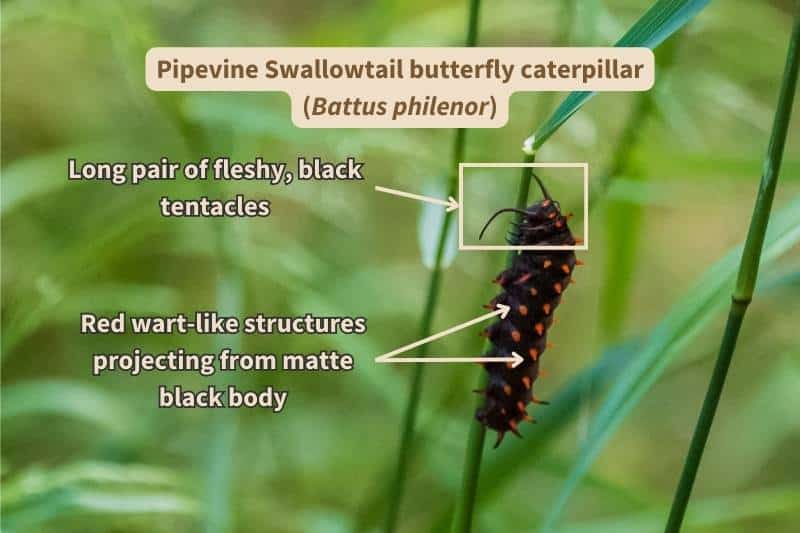

- Pipevine Swallowtail caterpillars are bizarre, alien-looking creatures covered in fleshy black tentacles.

- They resemble velvet worms, which are unrelated creatures classified in phylum Onychophora.

- The ranges of velvet worms and Pipevine Swallowtail butterflies overlap in tropical forests.

- Velvet worms are predatory. They hunt by shooting strings of sticky slime from their heads at their prey (Wagner, 2005) (Hickman et al., 2006).

- Pipevine Swallowtail caterpillars eat plants and don’t hunt other animals. It’s possible that they gain some protection from predators by mimicking velvet worms.

- Another common name for Pipevine Swallowtail butterflies is “Blue Swallowtail” (Pyle, 1981).

How Are Pipevine Swallowtail Butterflies Classified?

| Kingdom | Animalia |

| Phylum | Arthropoda |

| Class | Insecta |

| Order | Lepidoptera |

| Family | Papilionidae (“swallowtails”, subfamily Papilioninae “swallowtails”) |

| Genus species | Battus philenor |

How Do I Know I’m Looking at a Pipevine Swallowtail Butterfly?

Appearance of Pipevine Swallowtail Butterfly Eggs

Female Pipevine Swallowtail butterflies lay orangish-brown eggs on the leaves of host plants. They lay their eggs either one at a time or in small clusters.

Appearance of Pipevine Swallowtail Butterfly Caterpillars / Larvae

Pipevine Swallowtail caterpillars are pretty wild-looking and instantly recognizable.

Their bodies are matte purplish black and grow to about 2 inches long (5 cm) long. A pair of reddish-orange warts decorate each abdominal section. The warts line up to form two rows of orange dots down the caterpillars’ backs. Fleshy projections that look like tentacles stick out all along their bodies. The tentacles behind their heads are almost twice as long as the ones on the rest of their bodies.

Pipevine Swallowtail butterflies are not just found in North Carolina, but are distributed across the United States, even into the coastal areas of California. Pipevine Swallowtail caterpillars are normally purplish black with soft red “horns,” they can develop mostly red or all red coloration in intensely sunny, hot conditions (Shapiro 2007).

North Carolina’s climate supports the standard purplish black form; the red forms are found in the western United States. These conditions are mostly seen in the western but development in intensely sunny, hot conditions induces mostly red or all red coloration.

B. philenor caterpillars can actively move the long, paired tentacles behind their heads. They use these movable tentacles to search for plant stems. The tentacles don’t seem to smell or taste the plants. Instead, they seem to sense touch and help the caterpillars expand their search area (Kandori et al. 2015).

Pipevine Swallowtail butterfly chrysalids are pale lavender or tan and about an inch long (28 mm). Each chrysalis has curves, angles, and “horns” (Pyle, 1981).

Appearance of Adult Pipevine Swallowtail Butterflies

Adult Pipevine Swallowtail butterflies are distinctive and easy to recognize. They are medium-sized butterflies and grow to wingspans between 2.75 and 4.0 inches (7.0 – 10.2 cm).

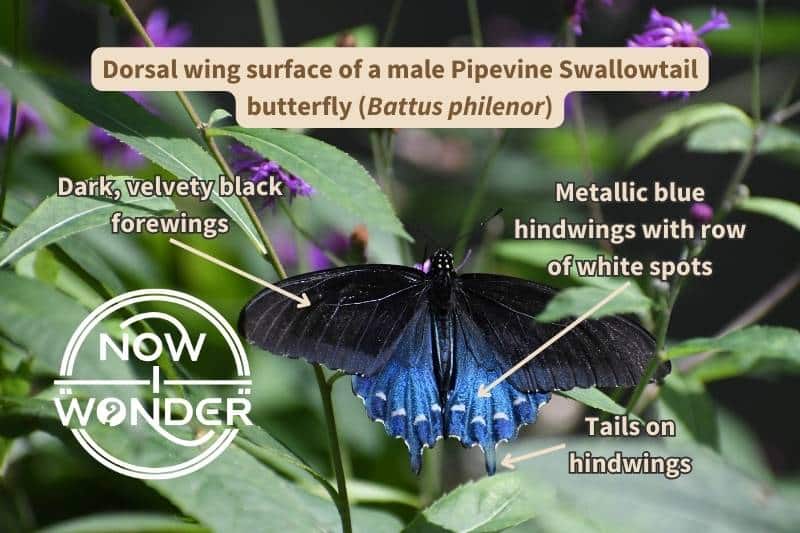

Males and females look slightly different from each other when seen from above. This is known as sexual dimorphism.

Both sexes have furry, deep black bodies. Their heads are black with white polka dots, and their eyes are black.

Both male and female Pipevine Swallowtail butterflies have velvety black forewings. The color is nearly solid, with almost no wing spots or patterning. At certain angles, you may see a faint line of pale wing spots running up the side of the forewings. But most of the time in the field, the top forewings of this species looks solid black.

The top of the hindwings is a different story.

Like many butterflies, the hindwings of Pipevine Swallowtails can appear to change color. The tiny scales that cover their wings reflect light at different angles. Sometimes the top surface of their hindwings look as black as their forewings. But when the sun strikes their wings just right, their wings turn metallic blue.

The iridescence is more obvious on male Pipevine Swallowtails than on females. It is the males that surprise observers with sudden flares of blue color.

Female Pipevine Swallowtail butterflies are duller overall than males. Their hindwings have more black than blue. A row of pale white spots runs along the hindwing margin on both sexes. But the spots are larger and more prominent on females than on males.

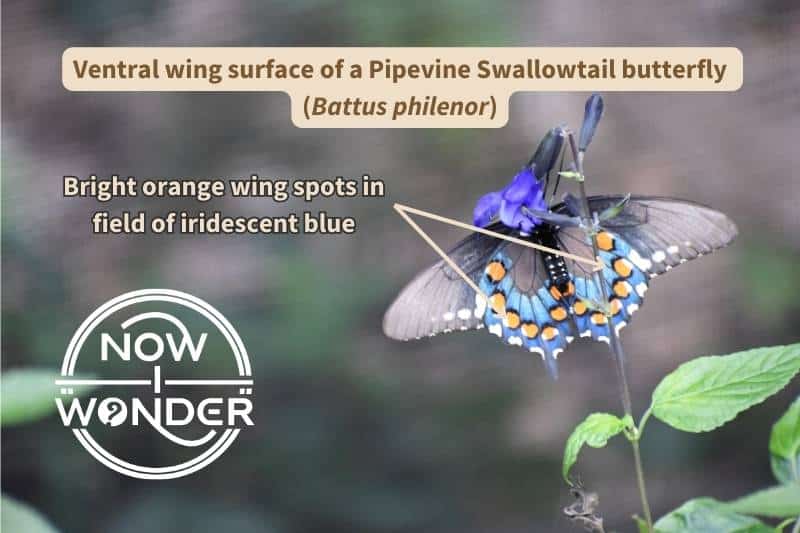

Pipevine Swallowtail butterflies look striking when seen from above. But the underside of their wings is even more colorful.

The ventral wing surfaces are dark close to their bodies. The outer half of their wings have a single row of large, orange spots in a field of bright, iridescent blue. The edges of their wings have white spots.

When Can I Find Pipevine Swallowtail Butterflies in North Carolina?

Adult Pipevine Swallowtail butterflies fly in North Carolina from early March to late November.

Where Should I Look to Find Pipevine Swallowtail Butterflies in North Carolina?

Pipevine Swallowtail butterflies live throughout North Carolina. They are most abundant in the western part of the state, in the Appalachian Mountains. Look for them in forests, especially near streams. Also search along the edges of thick woods.

- Pipevine Swallowtail butterflies aren’t as easy to find in the wild as some species. There are several reasons for this:

- First, these butterflies are very active. They don’t stay still for long. They flit from flower to flower quickly, and constantly flutter their wings.

- Second, they are dark-colored and live in forests. Their incredibly beautiful iridescence only appears in certain light. The dappled light in forests can hide these butterflies from casual observers.

- Third, they are creatures of deep woods. Most butterflies are creatures of open, sunny meadows and fields. But Pipevine Swallowtail butterflies don’t usually come out into wide, open areas.

Spotting a Pipevine Swallowtail in the wild is a real treat.

What Do Pipevine Swallowtail Butterflies Eat?

Pipevine Swallowtail Caterpillar Food Plants

Pipevine Swallowtail caterpillars are specialist feeders. They feed only on plants within the Birthwort family of plants (Aristolochiaceae). In North Carolina, their primary food plant is a birthwort species called Dutchman’s Pipe (Aristolochia macrophylla).

Dutchman’s Pipe is a high, climbing vine that grows in moist woodlands and along streams. The plant blooms with large, S-shaped purplish-brown flowers from April to June. Its heart-shaped leaves can grow 6 – 15 inches long (15.2 – 38 cm). The vine itself can climb to more than 65 feet (25 meters) (Niering and Olmstead, 2001).

Dutchman’s Pipe vines grow mostly in the Appalachian Mountains of western North Carolina. They are present in the Piedmont but more rare. The population density of Pipevine Swallowtail butterflies in North Carolina mimics this pattern. They are more common in the western part of the state than closer to the coast.

Adult Pipevine Swallowtail Butterfly Food

Adult Pipevine Swallowtail butterflies eat nectar from flowers. They particularly like nectar from honeysuckles, milkweed, and thistles (Pyle, 1981).

- Some North Carolina plants in these families include:

- Southern Bush Honeysuckle (Diervilla sessilifolia)

- Trumpet Honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens)

- Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata)

- Yellow Thistle (Cirsium horridulum)

- Bull Thistle (Cirsium vulgare)

Pipevine Swallowtail butterflies also like Butterfly-Bush (Buddleia spp.) nectar (Pyle, 1981).

References

Fordyce, James A., Zachary H. Marion, and Arthur M. Shapiro. 2005. “Phenological Variation in Chemical Defense of the Pipevine Swallowtail, Battus Philenor.” Journal of Chemical Ecology 31 (12) (12): 2835-46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-005-8397-9.

Hickman Jr., Cleveland P., Roberts, Larry S., Larson, Allan, L’anson, Helen, and Eisenhour, David J. 2006. Integrated Principles of Zoology. 13th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Companies.

Kandori, Ikuo, Kazuko Tsuchihara, Taichi A. Suzuki, Tomoyuki Yokoi, and Daniel R. Papaj. 2015. “Long Frontal Projections Help Battus Philenor (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae) Larvae Find Host Plants.” PLoS One 10 (7) (07). doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0131596.

Niering, William A., Olmstead, Nancy C. 2001. National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Wildflowers, Eastern Region. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

Pyle, Robert Michael, 1981. National Audubon Society Field Guide to Butterflies. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

Shapiro, Arthur. Field Guide to Butterflies of the San Francisco Bay and Sacramento Valley Regions, University of California Press, 2007.

Wagner, David L., 2005. Princeton Field Guides: Caterpillars of North America. Princton, NJ: Princeton University Press.