Few things in the natural world combine excitement and horror quite like big spiders. While most spiders are fairly small and often easily overlooked, some members of the spider order Araneae are absolute doozies. It’s both natural and a lot of fun to wonder how big the biggest spider in your area can get. So what is the biggest spider in North Carolina?

The biggest spider in North Carolina is the female Hogna carolinensis, known commonly as the Carolina wolf spider. Found throughout the southeastern United States, females can reach body lengths of 35.0mm (1.38in). This species is also the largest of the wolf spider family (Lycosidae).

Read on to learn about the Carolina wolf spider, North Carolina’s biggest spider.

Female Carolina wolf spiders are bigger than males

Spiders are sexually dimorphic, which means that males and females look different from one another in at least one way.

Spider sizes are traditionally given as “total body length” of their two body segments (the “prosoma” or head end, and the “opisthosoma” or rear end). Like many spider species, female Carolina wolf spiders are much larger than males.

Male Carolina wolf spiders average 19.0mm (0.75in), which is a substantial size and big enough that you’d definitely notice if one skittered across your hand. However, this is nowhere near the size of the females, which can top out at an impressive 35.0mm (1.38 inches).

To give an idea of scale, this makes the bodies alone of mature female Carolina Wolf spiders approximately the size of a Wheat Thin(TM) cracker. Add on their eight, long, seven-jointed legs and one of these spiders can span the palm of your hand.

While other wolf spiders grow to sizes that most people would characterize as “large”, none come close to Hogna carolinensis. For comparison, the next largest lycosid spider species found in North Carolina is the woodland giant wolf spider (Tigrosa aspersa), whose females grow to 25.0mm (0.98in) – a full 10mm (0.39in) smaller.

Carolina wolf spiders are big, brown, and hairy

At first glance, Carolina wolf spiders are nearly all brown, with very little color variation or patterns. What body patterns they have tend to be subtle and require close viewing to really resolve. This drab coloration helps them blend into the dirt as they lurk in their burrows.

If you look closely, the opisthosoma is slightly paler than the brown of the prosoma and marked with a dark heartspot. Unless you encounter a dead Carolina wolf spider, you’re not likely to catch a glimpse of its underside, otherwise known as its ventral surface. But if you could, you would see that their ventral opisthosomas are black and their legs are banded with varying patterns of alternating black and brown, depending on the sex. The end segments, called the tarsi, of their legs are black on both sexes.

One of the most common ways spiders differ visually is their chelicerae. These are the paired organs on the front of their prosomas, usually beneath their eyes, and which hold their terminal fangs. The chelicerae of Carolina wolf spiders are covered in yellowish hairs, although these hairs can appear nearly red on some mature females.

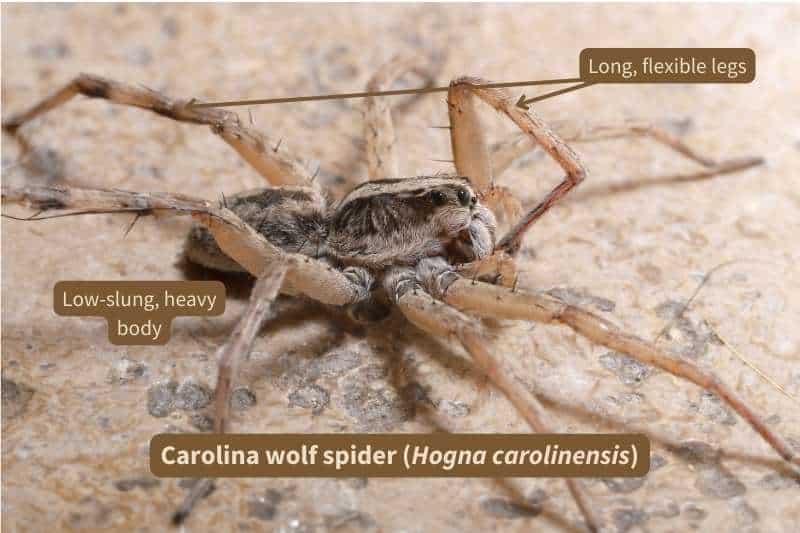

Carolina wolf spiders have long, sturdy legs

Carolina wolf spiders are large all over. While they are the largest spider in North Carolina based purely on the standard way spider size is measured (i.e. combined length of prosoma and opisthosoma), their legs add significantly to their overall size.

These spiders have long, thick legs that arch out from their bodies and their bodies are slung low between them. This leg anatomy gives them both stability and a long stride length, which helps them cover rough ground quickly and chase down their prey.

Like all spiders, their legs are made up of seven segments each, and spiders can control the movement of each leg both finely and independently. Carolina wolf spiders can extend their legs to help them clamber over obstacles or bend them close to their bodies so they fit easily into their underground burrows.

Carolina wolf spiders hang out in burrows

During the day, Carolina wolf spiders hide in burrows dug into the ground. Often their burrow entrances are around 30mm (1.2 inches) (Bradley, 2012), and topped with web strands into which grass or small twigs are stuck as camouflage.

The spiders crouch within their burrows facing the entrance, with their second, third, and fourth leg pairs pulled in close and their front-most pair slightly extended. In this way, the wolf spiders are best able to spot potential danger, and either burst from their burrows to flee or prepare to fight without having to guard their flanks and rear.

Despite being the biggest spider in North Carolina, Hogna carolinensis is still vulnerable to predators larger than themselves so keep low profiles when in their burrows.

Carolina wolf spiders hunt at night

While Carolina wolf spiders hide from predators during the day, they come alive at night. They are part of the ground active hunter guild of spiders, which means they chase down their prey from the ground.

Hogna carolinensis spiders live in open areas, such as pastures, meadows, and farm fields. They emerge from their burrows at night and go on patrol for prey, often wandering a fair distance from their protective burrows. Like many wolf spiders, they spend much of their time motionless, waiting for prey which they sense either by spotting movement or by feeling ground vibrations with their legs. If they don’t sense any prey within attack distance, they move to a different location and repeat the process until they locate a suitable meal.

Carolina wolf spiders are large enough to attack a wide variety of prey but are especially fond of common house crickets (Acheta domesticus). Wolf spiders lie in wait for prey to wander close, then lunge across the gap to attack. They bite and kill small prey immediately but may grapple with larger prey until they can corral the prey within their legs, then deliver the killing bite.

Carolina wolf spiders are hard to find

Because they come out mostly at night, actually seeing North Carolina’s biggest spider in the wild is pretty tough.

Even if you make a concerted effort to find and stake out a likely habitat, they will be hard to spot. We humans need a certain amount of light to see and, as big as they are, Carolina wolf spiders see much better in the dark than we do. They evolved as nocturnal hunters, while our vision is much better suited to the bright light of day. The light from a flashlight that shines brightly enough for you to see what you’re looking at is likely bright enough to scare a Carolina wolf spider back into its burrow.

If you are lucky enough to note the spot it disappears, you may be able to shine your flashlight into the burrow and spot the eye shine of at least several of its eight eyes glaring back at you. Just don’t be surprised if the spider rears back and flares its fang-tipped chelicerae at you. This is a classic wolf spider warning posture and it means “back off partner, I’m warning you” in no uncertain terms.

I imagine seeing the state’s biggest spider baring its fangs at you in a dark and lonely field might be a tad disconcerting. Personally, I choose to let the night belong to Hogna carolinensis.

If you’re intrigued by the idea of observing wolf spiders but aren’t up for nighttime stakeouts or would prefer to start a little smaller than the largest species in North Carolina, take heart. One of Hogna carolinensis’ smaller cousins, the rabid wolf spider, is often active during the day and is much more common. While not built on the scale of the Carolina wolf spider, rabid wolf spiders (Rabidosa rabida) are not what anyone would call “small”. To learn more about this species, check out this other Now I Wonder post “What are wolf spiders?“.

Related Now I Wonder Posts

For more information about spiders in general, check out these other Now I Wonder posts:

- What are wolf spiders?

- Jumping Spiders #1 – An Introduction

- Jumping Spiders #2 – A look at their incredible vision

- Jumping Spiders #3 – A detailed look at a special skill: Jumping

- Jumping Spiders #4 – As Predators

- Jumping Spiders #5 – As Prey

- Are spiders bugs?

- Do spiders have teeth?

- Do spiders have blood?

For more information about various spider species found in the southeastern United States, check out these other Now I Wonder posts:

For more information about spider relatives in class Arachnida, check out these other Now I Wonder posts:

References

Bradley, Richard A.. 2012. Common Spiders of North America. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Rose, Sarah. 2022. Princeton Field Guides Spiders of North America. Princeton: Princeton University Press.