People use the term “bug” to refer to a wide variety of creatures, including spiders. It is an informal term that many of us use loosely in the course of conversation, especially when we spot some multi-legged creature scurrying across our path. However, the term “bug” actually has a distinct meaning in zoology.

Spiders are not bugs. A “bug” is formally defined as an insect within order Hemiptera. Spiders are arachnids within order Araneae. While both share certain broad characteristics and are classified as arthropods in phylum Arthropoda, spiders and true bugs differ in many important and visible ways.

Both spiders and true bugs are extremely important in the ecosystems of the natural world but they are very different creatures. This post covers the visible differences between the two orders so that you can go beyond seeing just “bugs”.

Spiders vs. True Bugs

Classification

Both spiders and true bugs are multi-cellular invertebrate animals classified in phylum Arthropoda and descended from a shared, ancient worm-like ancestor (Arnett Jr. and Jacques Jr. 1981). Their classification is further divided by class, with spiders belonging to class Arachnida and true bugs belonging to class Insecta. This class-level split separates spiders from true bugs.

Moving a step down in the classification hierarchy, spiders are in order Araneae while true bugs are in order Hemiptera. This refinement doesn’t differentiate them from each other – that happened at the class level. Instead, the order level of classification differentiates spiders from other arachnids such as scorpions and mites, and true bugs from other insects such as grasshoppers and beetles.

Both orders contain numerous families, genera, and species. Order Araneae contains approximately 42,000 species worldwide (Britannica 2017), with about 3,000 species found in North America (Mile and Mile 1980). Worldwide, order Hemiptera represents approximately 23,000 species, with about 4,500 North American species (Imes 1992).

Body shape and segmentation

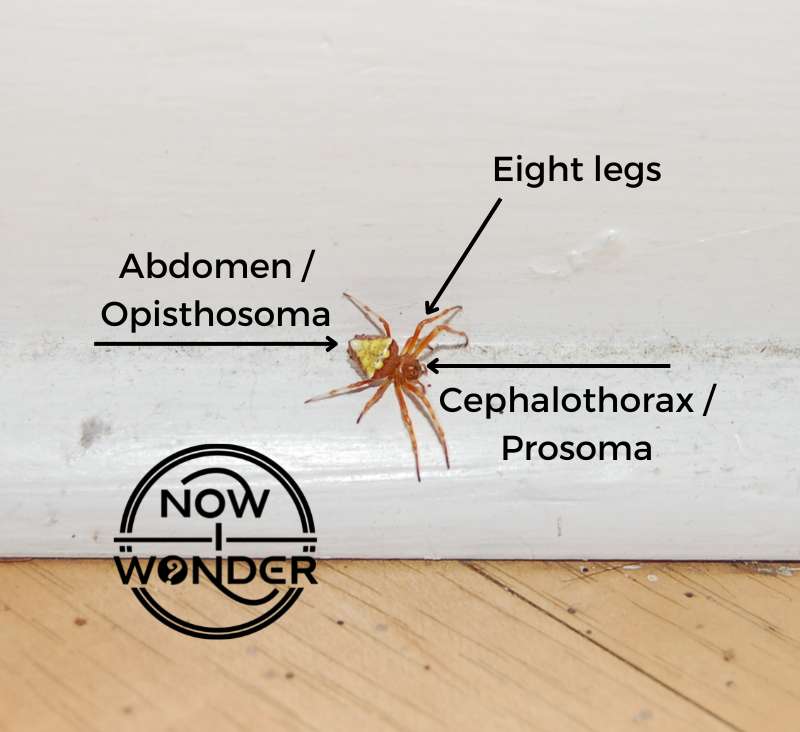

A fundamental difference between spiders and true bugs is the shape and segmentation of their bodies. Both have segmented bodies but spiders only have two segments, while true bugs have three.

Spider bodies are divided into a cephalothorax (also called an prosoma), which represents a fused head and thorax, and an abdomen (also called an opisthosoma).

In contrast, true bug bodies are divided into a head, a thorax, and an abdomen. A spider’s two segments are usually extremely obvious no matter what perspective it is viewed from while a bug’s three segments tend to be most visible when looking at its underside.

Legs

Another fundamental and extremely obvious difference between spiders and true bugs is their legs.

Both are arthropods, which literally means “jointed foot”, and the legs of both creatures are multi-jointed with visible segments.

However, spiders have eight legs while true bugs have six.

Spider legs are always attached to their cephalothorax section, never to their abdomens. Bug legs are always attached to their thorax (the middle body segment), which is further divided into the prothorax, mesothorax, metathorax sections (Arnett and Jacques 1981). Each pair of legs is attached to one of these thoracic sub-sections.

Another, less obvious, difference between the legs of spiders and those of true bugs are the number of segments on each leg. Spider legs are made up of eight sections:

- Coxa (base section that attaches the leg to the prosoma)

- Trochanter

- Femur

- Patella

- Tibia

- Metatarsus

- Tarsus

- Tarsal claws

Hemipterans have all of these leg sections except the patella. Also, while both animals have jointed feet by definition as arthropods, their feet are slightly different. Spiders can have 2 or 3 claws on each leg depending on the species (Rose 2022) and their tarsae usually bear bristles, whereas true bugs have a pair of claws plus a pad (Milne and Milne 1980).

Eyes

True bugs have a pair of faceted compound eyes, which can see motion, color, and assess distance, and simple eyes called “ocelli”, which primarily sense changes in light and day length. The eyes of true bugs are usually positioned in the same places on their heads.

In contrast, the majority of spiders have 8 eyes, although a few species have only 2 or none at all, arranged in distinct patterns on the head that help differentiate spiders as belonging to different families.

One example is the eye arrangement unique to jumping spiders in family Salticidae. To see an example, check out the second of the series of 5 Now I Wonder posts on these remarkable spiders “Jumping Spiders #2 – A look at their incredible vision“.

Antennae

Another major difference between the heads of spiders and those of true bugs is that hemipterans have a pair of antennae on their heads, which spiders lack. Antennae are segmented sensory organs that are used mostly for smell and touch but sometimes for hearing; on true bugs, they tend to be long and are located at the front of the head between their compound eyes.

Mouthparts

All spiders are predators, with the exception of ghost spiders (family Anyphaenidae) and prowling spiders (family Miturgidae) (Bradley 2012), but must liquefy prey tissue in order to eat.

True bugs eat plants, such as plant bugs (family Miridae), blood, such as bed bugs (family Cimicidae), or animals, such as assassin bugs (family Reduviidae). However, true bugs also evolved to consume only liquid food.

Both spiders and true bugs suck liquid from their food sources and hold their mouthparts in grooves under their heads, flipping them up when they are ready to feed.

However, despite these similarities the mouthparts of spiders and true bugs differ significantly.

Spider mouthparts consist of:

- Chelicerae: stout paired appendages above the actual mouth that are tipped with the venomous fangs spiders use to subdue or kill their prey.

- Pedipalps: paired appendages used to crush prey and tipped with sensory nerves; in males of some species, pedipalps are modified for sperm transfer.

True bug mouthparts consist of:

- Mandibles: paired structures with sharp teeth that close side to side used to pierce the outer tissue of plant or prey. Located on the outer side of the mouth.

- Rostrum: also called a beak or a proboscis, this is a dagger-like structure made up of a pair of maxillae, which are tubes that fit together to form two canals. Saliva and digestive juices flow into the food source through one canal while the bug sucks the food up through the other.

Wings

Spiders are never winged. In contrast, and like most insects, true bugs have two pairs of wings attached to the mesothorax and metathorax (Arnett and Jacques 1981). Their forewings have thickened, leathery bases and membranous tips. This set of wings fold flat in a criss-crossed shape over their backs and cover the hindwings. The hindwings are used for flying, are slightly shorter than the forewings, and always fully membranous.

Growth and Development

Spiders and true bugs also share some aspects of their growth and development.

Both are terrestrial animals that hatch from eggs laid by females and fertilized by male sperm.

Both have exoskeletons made of a material called chitin, which consists of two layers: a rigid, durable outer cuticle and a softer inner cuticle. Spider exoskeletons tend to be thinner and more flexible than those of insects, especially on the abdomen.

Both spiderlings and hemipteran young (called nymphs) resemble adults, although nymphs lack adult wings, and both must undergo periodic molts to grow to adult size. During a molt, the spider or bug sheds its constricting exoskeleton which frees its body long enough to increase body size before the cuticle hardens again. Depending on the species, spiders undergo 5 – 10 molts before reaching adulthood (Bradley 2012); nymphs go through 5 stages called “instars” (Milne and Milne 1980).

Sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is when males and females of the same species look different. Spiders are sexually dimorphic in color and especially in size. Females are huge compared to males. One example is the golden silk orbweaver spider (Trichonephila clavipes); females can be more than an inch longer (more than 25 mm) than males.

In contrast, some true bugs may exhibit small size variations between males and females but any difference is extremely slight.

Conclusion

Referring to a spider as a “bug” remains tempting because many small, multi-legged creatures appear similar at first glance. However, spiders and true bugs are not the same at all. It is much easier to appreciate each creature for the natural wonder it is when you know the real differences between a spider and a bug.

Related Now I Wonder Posts

For more information about spiders, check out these other Now I Wonder posts:

- What are wolf spiders?

- Jumping Spiders #1 – An Introduction

- Jumping Spiders #2 – A look at their incredible vision

- Jumping Spiders #3 – A detailed look at a special skill: Jumping

- Jumping Spiders #4 – As Predators

- Jumping Spiders #5 – As Prey

- Do spiders have teeth?

- Do spiders have blood?

For more information about spider relatives in class Arachnida, check out these other Now I Wonder posts:

References

Arnett Jr. RH, Jacques Jr. R. 1981. Simon & Schuster’s guide to insects. New York (NY): Simon & Schuster Inc.

Bradley, Richard A. 2012. Common spiders of North America. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Imes R. 1992. The practical entomologist. New York (NY): Quarto Publishing plc.

Milne l, Milne M. 1980. National Audubon Society: field guide to insects &spiders North America. New York (NY): Chanticleer Press, Inc.

Rose S. 2022. Princeton Field Guides: spiders of North America. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press.

“spider.” In Britannica Concise Encyclopedia, by Encyclopaedia Britannica. Britannica Digital Learning, 2017.