Grasshoppers are common insects throughout the United States. If you’ve ever been startled by a grasshopper leaping out from underfoot as you walk through a garden or meadow and wondered what it does all day, this post will help.

In the early morning, grasshoppers bask in the sun to warm up. They spend the day eating plants, avoiding or escaping predators and mating. Females also lay their eggs. Mid to late afternoon, they bask in the sun again until evening and then take shelter for the night.

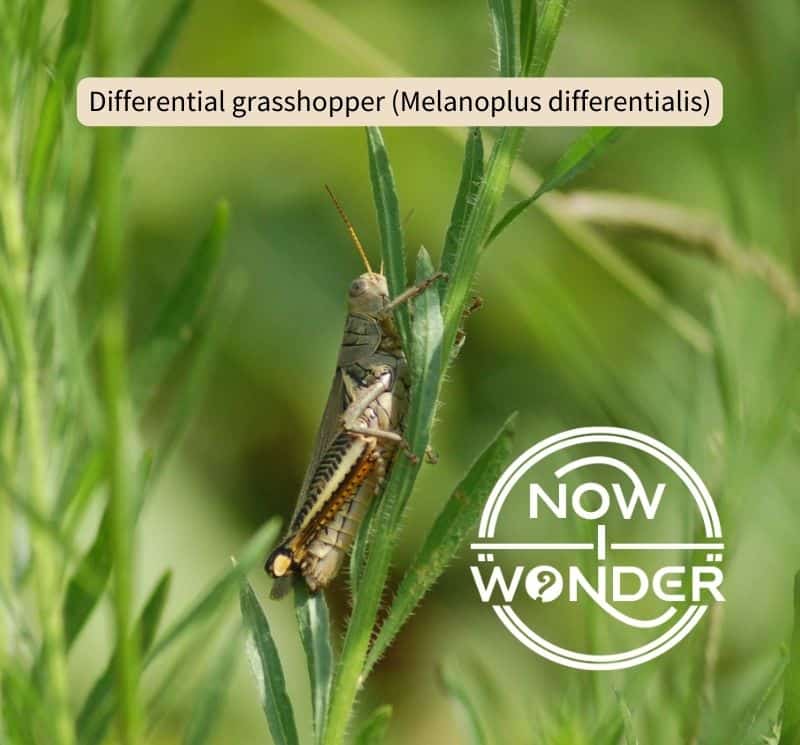

More than 400 species are native to North America and they can be found in nearly all habitats from spring through fall. Two common short-horned grasshoppers found in the southeastern United States are the eastern lubber grasshopper (Romalea guttata) and the differential grasshopper (Melanoplus differentialis). Read on to learn more about the daily lives of grasshoppers, with these two species as examples.

Grasshoppers bask in the sun

Grasshoppers are insects and therefore “ectothermic”, which means they are unable to regulate their body temperature by themselves. They are sensitive to temperature and become sluggish anytime the temperatures are cooler than optimal, such as during the night and on rainy days.

Anytime they get too cold, grasshoppers warm themselves up by “basking”. They orient their long, narrow bodies broadside to the sun so that the rays fall on the largest surface area, much like humans stretch out on the ground to tan. Once warmed up, they walk, jump and fly faster, which makes it harder for predators to catch them.

Grasshoppers start eating

Unlike some grasshoppers, eastern lubber grasshoppers don’t mind being close to each other so will feed in groups on the same plant if it is the most convenient food source.

Eastern lubber grasshoppers are unable to fly; they are so big and heavy that their wings are too small to generate enough lift for flight. At up to 70 mm (2.75 inches) in length, these grasshoppers walk everywhere they want to go. While they can cover a lot of ground quickly and are good climbers, the inability to jump or fly long distances mean that their range is limited compared to some other grasshopper species.

In contrast, differential grasshoppers are strong jumpers and fliers. At up to 44 mm (1.75 inches), they are smaller and less bulky than eastern lubbers and can choose to walk, jump or fly to their food plants. Both jumping and flying covers distance faster than walking so differential grasshoppers can feed across a wide area during the course of a day.

Grasshoppers eat for hours at a time

Most grasshoppers within family Acrididae are “phytophagous”, which means that they feed on plants to get the energy required for growth and reproduction.

Eastern lubber grasshoppers eat a wide variety of plants, including such important agricultural crops like fruit trees, ornamental flowering plants, and vegetables, especially broccoli, Brussels sprouts, carrots, peas and squashes.

Differential grasshoppers normally favor grasses and weeds over cultivated crop and ornamental plants. However, they can become major pests of crops such as corn, soybeans, alfalfa, cotton and grains during times of drought when their wild food plants begin to die off.

Grasshoppers try to avoid being eaten

Grasshoppers are large insects and eaten by a wide variety of predators. Grasshoppers have developed several strategies to ensure that their species survives year after year.

Eastern lubber grasshopper can escape predators only by running and climbing out of reach which makes them more vulnerable to predation than other species like differential grasshoppers. To counter this disadvantage, eastern lubber grasshoppers evolved the ability to make and store toxins in their bodies.

These grasshoppers are boldly colored in yellow, orange and black, with red stripes running the length of their fore wings. This vivid color pattern is a defense strategy called “aposematic coloration” and acts as a visual warning to predators, advertising the grasshoppers’ toxicity.

Eastern lubber grasshoppers are poisonous. They evolved the ability to create and store toxins inside their bodies. If a predator ignores the warning signaled by the grasshopper’s bright colors and attacks, the grasshopper secretes a toxic froth through their breathing spiracles, which can sicken or kill the predator if ingested.

When seized, an eastern lubber grasshopper will also flare its wings, hiss and kick out with its strong hind legs. Its legs are edged with spines sharp enough to cut human skin; sometimes the combined effect of surprise and pain can startle a predator into releasing the grasshopper.

In contrast, the differential grasshopper did not evolve toxins or bright colors to deter predators so must rely on other methods to avoid being eaten. They are usually green or brown to blend into the vegetation and can both jump and fly very well.

These insects can jump up to 40 feet and change direction abruptly in mid-air which can help them evade predators. If seized, they will regurgitate the contents of their crop. The crop is the insect equivalent of the human stomach and the contents are brown, acidic and smelly. Sometimes, this is enough to deter a predator’s attack.

Many individual grasshoppers are eaten despite these strategies. Here is a list of common predators:

- Insectivorous birds such as the Loggerhead Shrike (Lanius ludovicianus)

- Red Foxes (Vulpes vulpes)

- Common Raccoons (Procyon lotor)

- Virginia Opossums (Didelphis virginiana)

- Striped Skunks (Mephitis mephitis)

- Eastern Gray Squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis) – occasionally

- Eastern Fence Lizards (Sceloporus undulatus)

Grasshoppers mate and lay eggs

Reproduction is a major concern for grasshoppers. Both eastern lubber and differential grasshoppers have a single adult generation every year. Both species must mate and lay their eggs before the start of winter and each evolved its own technique for attracting mates.

Male grasshoppers rub the rough surfaces of their fore and hind wings together to create a loud, low buzzing noise which attracts females. Mating male and female grasshoppers often stay connected for several hours and the smaller males can often be seen perched on the females’ backs as they mate.

After mating is complete, the female will locate a suitable patch of ground and begin laying her eggs. She drives her ovipositor – the pointed reproductive organ located at the tip of her abdomen through which female insects lay eggs – through the ground to the correct depth. She lays the eggs, then scrapes the soil over the hole and moves on.

Female grasshoppers lay many eggs. A single differential grasshopper female can lay over 80 eggs in a season. (Milne, L. and Milne, M. 1980)

Grasshoppers must devote their resources to creating as many young as possible in a short period of time since the adults survive only one season and the larvae receive no parental care. The sheer number of eggs laid ensures that at least some of the larvae will survive to adulthood.

Grasshoppers move out of reach until dawn

Grasshoppers risk being eaten both day and night. Both eastern lubber and differential grasshoppers avoid ground-based predators such as skunks by climbing to the tops of tall plants at night. Unfortunately, some nocturnal predators like opossums and raccoons are great climbers so this strategy is not always effective.

An individual grasshopper’s goal for every day is short and to the point: stay alive long enough to mate. As an Order, these insects have evolved diverse strategies to attain that goal. While the strategies aren’t always successful for every individual, enough grasshoppers survive from one day to the next to ensure that their species survives year after year.

Related Now I Wonder Posts

For more about grasshoppers and other insects in order Orthoptera, check out these other Now I Wonder posts:

- What is the difference between grasshoppers and locusts?

- What’s the difference between a grasshopper and a katydid?

- What is the difference between cicadas and grasshoppers?

- Grasshoppers vs. crickets

For information about insects in general, check out these other Now I Wonder posts:

- Do insects ever eat spiders? Part 1: Attacks from the air

- Do insects ever eat spiders? Part 2: Attacks from the ground

- Do insects have blood?

References

Evans, Edward W. Utah Pests Fact Sheet. Utah State University Extension, 2008. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjs-5WY-M33AhW5s4QIHZDDD_0QFnoECBAQAw&url=https%3A%2F%2Fagresearch.montana.edu%2Fwtarc%2Fproducerinfo%2Fentomology-insect-ecology%2FGrasshoppers%2FUtahFactSheet.pdf&usg=AOvVaw1CjoHwqMTo3CUE_8n5dCXt

Capinera, John L., “Eastern Lubber Grasshopper.” In Handbook of Vegetable Pests. Elsevier Science and Technology, 2001.

Cranshaw, W. and Shetlar, D. “Grasshoppers.” In Garden Insects of North America. 2nd ed. Princeton University Press, 2017.

Ingrisch, Sigfrid, and D. C.F. Rentz. “Orthoptera.” In Encyclopedia of Insects, edited by Vincent H. Resh, and Ring T. Carde. 2nd ed. Elsevier Science & Technology, 2009.

Lagasse, Paul. “Grasshopper.” In The Columbia Encyclopedia, 8th ed. Columbia University Press, 2018.

Milne, L. and Milne, M. National Audubon Society Field Guide to Insects and Spiders: North America. Chanticleer Press, Inc. 1980, 36th Printing, 2021.

Missouri State University Extension, http://extension.msstate.edu/newsletters/bug%E2%80%99s-eye-view/2016/carolina-grasshopper-vol-2-no-31

University of Florida, https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/orn/lubber.htm

University of Wyoming, Grasshoppers of Wyoming and the West, http://www.uwyo.edu/entomology/grasshoppers/field-guide/dica.html