If you spend enough time looking closely at nature, you may spot a creature that looks a little bit like a grasshopper and a lot like a “leaf-with-legs”. These are katydids and if you wonder what katydids are and how they relate to more familiar grasshoppers, this post will help.

Katydids are nocturnal insects with long antennae whose wings can mimic plant leaves. Grasshoppers are diurnal insects with shorter antennae. Katydids are “long-horned grasshoppers”; grasshoppers are “short-horned grasshoppers”. Both are classified in different families within Order Orthoptera.

Both katydids and grasshoppers are technically “grasshoppers” as both as classified within Order Orthoptera. They are split into different Families based on the length of their antennae. Katydids are classified in Family Tettigoniidae while grasshoppers are classified in Family Acrididae. However, these insects differ from each other in more ways than just the length of their antennae. Read on to learn more about what makes katydids and grasshoppers different.

Comparison of Katydids vs. Grasshoppers

| Common name | Grasshopper | Katydid |

| Family | Acrididae | Tettigoniidae |

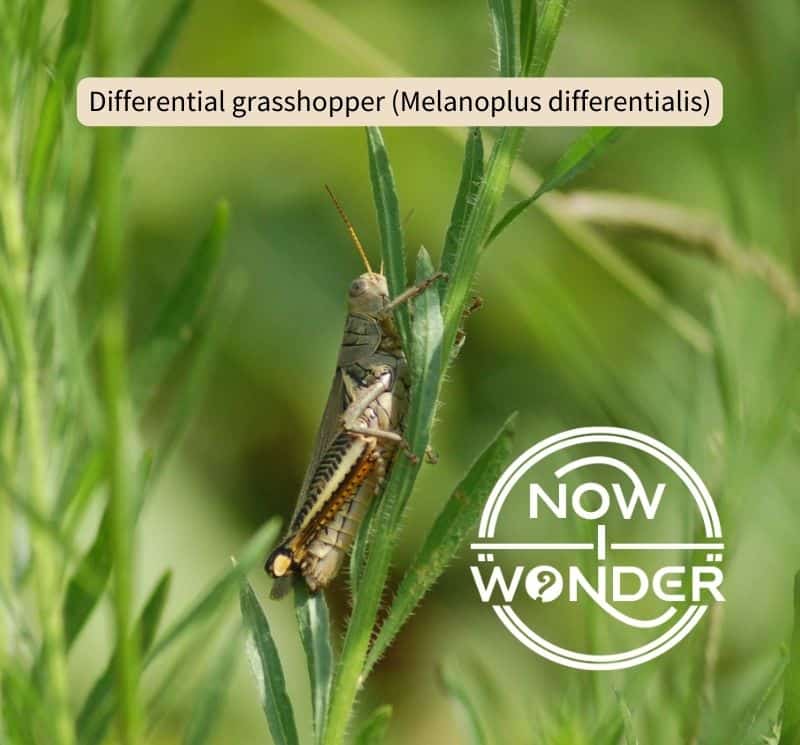

| Example species for comparison | Differential Grasshopper (Melanoplus differentialis) | True Katydid (Pterophylla camellifolia) |

| Size in mm of example species | 28-44 mm | 45-55 mm |

| Size in inches of example species | 1.125-1.75 in | 1.75-2.125 in |

| Description | Body is yellowish-brown, shiny, antennae either brownish yellow or red. Hind femora has distinctive black herringbone pattern. Wings extend to end of abdomen. Dark eyes. | Body is leaf green, fore wings are oval and look like veined leaves. Top of head comes to a point. |

| Habitat | Grasses, shrubs | Deciduous trees |

| Range | Common throughout United States | Eastern United States, north to Massachusetts, south to Florida, west to Texas. |

| Food | Primarily grasses. Will feed on crops, especially corn and soybeans. | Foliage of deciduous trees. |

| Notes | Don’t migrate. Destructive. | Both sexes sing; easily heard. |

Antennae are different lengths

Katydid antennae are much longer than those of short-horned grasshoppers. Grasshopper antennae are less than 30 segments long, while katydid antennae have more than 30 segments (Ingrisch 2009) and are sometimes longer than their bodies.

Ovipositors are different sizes

An “ovipositor” is the organ through which female insects lay their eggs.

Female katydids have highly visible, long, spike- or sword-like ovipositors at the end of the abdomens. These organs are much longer than those of short-horned grasshoppers, which are either barely visible or retracted into the female’s abdomen, depending on the species.

The differences in ovipositor size and shape evolved to support how each group lays its eggs.

Short-horned grasshopper females lay their eggs in the soil. They use their short, sturdy ovipositors to drive into the soil to the correct depth before laying their eggs.

Katydid females lay their eggs in plants. They use their long, sharp ovipositors to slice open tender twigs or leaves and then deposit their eggs in the slit.

Evolved different survival strategies

Katydids evolved over time so that their wings and bodies look like plant leaves, often to a startling degree. These insects, such as the True Katydids, can look exactly like green leaves with legs, right down to paler green lines imitating leaf veins.

Katydids need this camouflage because they rest during the day. A katydid can lessen its risk of spotted by a predator and eaten by staying motionless and pretending to be just one of thousands of green leaves. This tactic can be very effective as only predators with sharp vision or good luck spot katydids as they rest. It is also why katydids are less familiar to most people than short-horned grasshoppers; we just don’t notice them as often.

In contrast, short-horned grasshoppers must move around during the day to eat and mate and do not have the option to hide motionless while daytime predators hunt.

Some short-horned grasshoppers are subdued shades of shades of green and brown, which helps them blend into their surroundings. For example, the Carolina Locust (Dissosteira carolina) is a short-horned grasshopper that likes to rest on bare ground. It is mottled brownish gray and becomes very difficult to see when motionless against the dirt.

Other grasshoppers display color patterns that look bold in isolation but serve to break up the insect’s outline when the insect is positioned in dappled light and other species stand out no matter what background they are seen against.

For example, the Eastern Lubber Grasshopper (Romalea guttata) is yellow, black, and red, and is poisonous to predators. It manufactures toxins that are powerful enough to sicken or kill predators and its vivid coloring visually warns predators against trying to eat them.

Camouflage is more important to katydids than grasshoppers. Most katydid species are poor jumpers and fliers and some can do neither. In contrast, most grasshoppers can try to escape predators by jumping or flying away. If seized, some grasshopper species hiss and flare their wings to startle the attacker into releasing them and kick their attacker with their spiny hind legs.

However, grasshoppers and katydids are still eaten by many predators who evolved ways to overcome their passive and active defenses.

Generate sound differently

With the exception of swarming locusts, grasshoppers and katydids are solitary insects, preferring to disperse over wide areas within suitable habitats. They use sound to communicate with each other over long distances.

Any organism that uses sound to communicate must be able to perform two separate but related functions; making sound and receiving sound.

“Singing” is very important to both grasshoppers and katydids as males sing to attract females for mating. Male grasshoppers produce sound by rubbing their hing legs against their wings. Katydids make sound by rubbing their fore wings against their hind wings.

Grasshoppers and katydids have two tympanic membranes on their bodies. These membranes are located on the front legs in katydids and on the first abdominal segment in grasshoppers. Roughly equivalent to a human’s ear drum, these membranes vibrate in response to sound waves and – when interpreted by the insects’ nervous systems – allows them to hear.

Eat different things at different times

In general, short-horned grasshoppers are plant-eaters, although some species feed on fungus instead. Individual locusts are known to eat other locusts but this is due to the dramatic behavior change they undergo when transforming into a swarm rather than their natural state. They are diurnal, which means active during the day, and feed on weeds, grasses and crop plants.

Most katydids are nocturnal and feed on leaves high up in the canopy at night. However, some species are carnivorous and active nocturnal predators of small insects.

Both short and long horned grasshoppers play important roles in nature and are related but different creatures. They can be significant pests due to their plant-eating lifestyles – some species cost agricultural interests millions in losses every year – and support many predator species, like birds and spiders.

Grasshoppers and katydids are found in warm environments all over the world. Whether noticed or not, short-horned grasshoppers fill warm summer days with their songs while long-horned katydids sing through the nights.

Related Now I Wonder Posts

For more about grasshoppers and other insects in order Orthoptera, check out these other Now I Wonder posts:

- What do grasshoppers do? A day in their life

- What is the difference between grasshoppers and locusts?

- What is the difference between cicadas and grasshoppers?

- Grasshoppers vs. crickets

For information about insects in general, check out these other Now I Wonder posts:

- Do insects ever eat spiders? Part 1: Attacks from the air

- Do insects ever eat spiders? Part 2: Attacks from the ground

- Do insects have blood?

If you’d like to hear how different species of katydids sound, click here to visit the University of Florida’s Natural Area Teaching Laboratory website.

References

Arnett, Ross H., Jacques Jr., Richard L. Simon & Schuster’s guide to insects. Simon & Schuster, Inc. New York. 1981

Eaton, ERic R. and Kaufman, Kenn. 2007. Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America. Mariner Books. HarperCollins.

Florida Natural Area Teaching Lab, University of Florida. “Katydids” https://natl.ifas.ufl.edu/biota/katydids.php

Hartbauer, M., M. E. Siegert, and H. Römer. 2015. “Male Age and Female Mate Choice in a Synchronizing Katydid.” Journal of Comparative Physiology 201 (8) (08): 763-772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00359-015-1012-9

Imes, R. The Practical Entomologist. Quarto Publishing, New York. 1992.

Ingrisch, Sigfrid, and D. C.F. Rentz. “Orthoptera.” In Encyclopedia of Insects, edited by Vincent H. Resh, and Ring T. Carde. 2nd ed. Elsevier Science & Technology, 2009.

“Katydid” The Hutchinson Encyclopedia. Abingdon: RM Education, Ltd., 2020.

Milne, L and Milne, M. National Audubon Society Field Guide to Insects and Spiders: North America. Chanticleer Press, Inc. 2021.

Montealegre-z, Fernando and Daniel Robert. 2015. “Biomechanics of Hearing in Katydids.” Journal of Comparative Physiology 201 (1) (01): 5-18. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00359-014-0976-1