Reptiles can overheat when they are unable to retreat to cooler areas and during periods of extraordinary heat. Many reptiles thrive in hot environments but all can die of heat stroke and dehydration if their body temperatures rise beyond their upper tolerance limits.

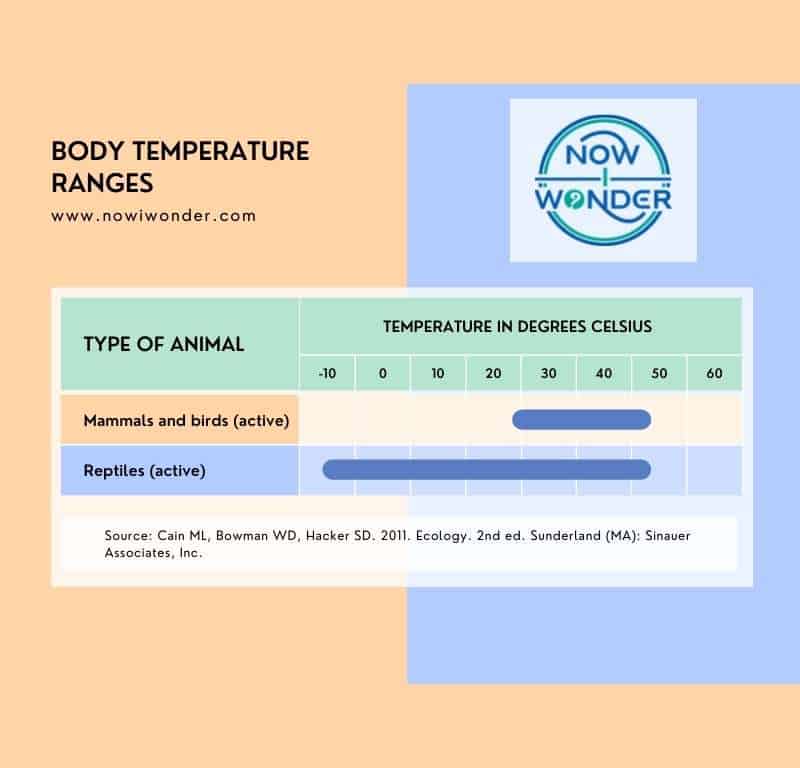

Every living organism has a range of temperature in which they function the best because the survival and functioning of living organisms is strongly tied to their internal temperatures.

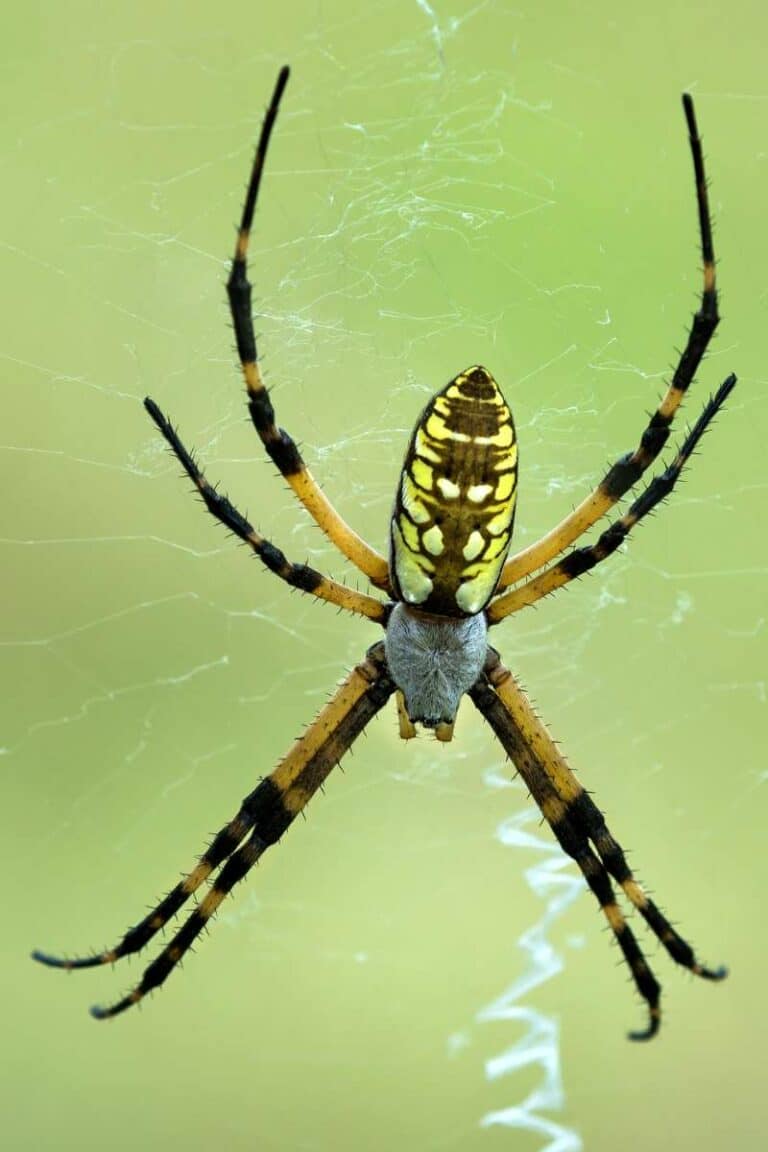

Reptiles can tolerate a wide body temperature range because they are cold blooded, or “ectothermic” animals; their body temperatures and activity levels adjust up and down in response to environmental temperatures.

As an animal’s body temperature rises beyond the top of its preferred temperature range, it first experiences “heat stress”. During heat stress, the animal senses that it is too hot and attempts to compensate for it. Animals can regulate their body temperatures either physiologically, through strategies like changing blood flow to increase evaporation from its skin, or behaviorally, such as relocating into shade.

If the animal can’t bring its body temperature down, it progresses to “heat exhaustion”. Heat exhaustion is a serious condition; the animal may have a fast, weak pulse, nausea or vomiting, fatigue, weakness, and dizziness.

The temperature at which heat exhaustion occurs varies by species, as do the symptoms, which may be more or less obvious. However, all animals experiencing heat exhaustion are in serious danger because they are losing normal function.

Unchecked heat exhaustion will progress to “heat stroke”, which is a medical emergency. Heat stroke is a complete collapse of an animal’s ability to regulate its body temperature and dissipate excess heat through evaporation.

Heat stroke is usually fatal in all animals without artificial medical intervention because by this point, the animal has lost both consciousness and all remaining ability to cool itself off.

How excess body heat causes symptoms

Enzyme changes

Every animal uses organic compounds to synthesize chemical energy required for growth, reproduction, and daily activities like finding food and escaping predators. The metabolic reactions that create this chemical energy depend on certain enzymes functioning properly and enzymes are temperature-dependent.

Enzymes are proteins that change the rate that chemical reactions occur without needing any additional energy added in. They fold into very specific shapes as a result of the chemical bonds between the atoms. An enzyme’s shape determines what other substances in the body it can connect with to create the end product of a chemical reaction, just like only certain keys can open certain locks.

At high temperatures, enzymes become “denatured”, which is when the bonds holding the enzyme into its specialized shape break. Once the enzyme’s shape changes, it can no longer do its job in the animal’s body and the animal can’t function as well anymore.

Most animals will die at temperatures lower than the temperatures at which their enzymes become denatured because the coordination required for these enzymes to even come into play break down sooner than the enzymes themselves (Cain et al. 2011).

Water volume changes

High temperatures influence the availability of water. Warmer air can hold more water vapor and water evaporates faster in warmer temperatures. So the rate at which land animals like reptiles lose water to their environment is related to air temperature.

How body temperature changes

Reptiles evolved a unique approach to managing their body temperatures compared to birds and mammals. This approach has a direct impact on whether – and at what point – they get too hot. Some aspects of reptilian thermoregulation will be covered here; for more detailed information, check out my post “Do reptiles have cold blood?“

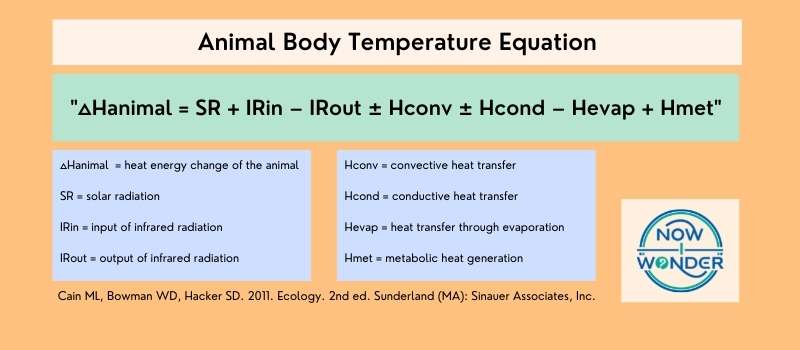

Every animal’s body temperature will rise when the amount of heat created, absorbed, and retained is higher than the amount it loses to its surroundings. Heat transfer and thermoregulation is complex and varies between types of animals, relates species, and even between individuals.

- Body heat is always gained through the chemical reactions of an animal’s metabolism. Reptiles don’t generate very much body heat at all; their metabolisms are very slow, “being one-fifth to one-seventh that of a mammals of equivalent size” (Doneley et al. 2018).

- Body heat can be either gained or lost through conduction, convection, and radiation, depending on the “thermal gradient”. The thermal gradient is the difference in temperature between the animal’s body and its environment. As heat always flows from hot to cold, the thermal gradient an animal experiences at any given time determines whether it will lose or gain body heat.

- Body heat is always lost through evaporation, which is when an animal’s body water disperses into the surrounding air by transitioning to a gas (Mares 1999). Evaporation reduces the animal’s blood volume but also carries a lot of body heat away.

Reptiles native to hot deserts evolved to tolerate much higher temperatures than mammals or even birds before beginning to experience heat stress.

For example, the desert iguana (Dipsosaurus dorsalis) found in the Great Basin, Mojave, and Sonoran deserts in the southwestern United States can remain active at temperatures up to 46 degrees Celsius (115 degrees Fahrenheit) (Behler and King 2020).

Reptile strategies for avoiding overheating

- Ability to change color: Many reptiles can lighten the color of their skin when exposed to lots of sunlight and its accompanying heat. The lighter color decreases absorption and helps the animals radiate heat.

- Black abdominal cavities: Sunlight contains ultraviolet radiation that penetrates body tissue and can damage cells. To counteract this risk, many desert lizards who are active during the day evolved a black lining on the inside of their abdominal cavities, which protects the internal organs by blocking the UV light (Mares 1999).

- Skin blocks evaporation: Reptile skin is scaly and dry, which prevents the reptile’s body water from evaporating into the surrounding air easily.

- Behavior changes: Depending on the species, a reptile may move into shade, retreat into underground burrows (sidewinder snake, Crotalus cerastes), bury themselves (fringe-toes Lizards, Uma notata), climb into bushes to find slightly cooler air (desert Iguana, Dipsosaurus dorsalis) , switch to being active at night when it is cooler, and going dormant under extreme conditions.

How reptiles get too hot

As impressive as the above strategies are, they can be overwhelmed. Even though reptiles can tolerate higher temperatures for longer than many animals, they still have an upper limit. Sustained, extraordinarily hot temperatures seen during freak weather events can overwhelm some individuals, especially if water becomes more scarce than usual.

Evaporation increases as the animal’s body temperature rises. This helps them cool down and maintain their preferred body temperature. But water is limited and evaporation can never be stopped completely. If an animal loses more water from its body through evaporation than it can replace, it will die of cardiovascular failure due to low blood volume and dehydration.

Reptiles can also get too hot if they are prevented from retreating from the heat. Extremely mobile reptiles which can climb well – like snakes and lizards – don’t usually have to worry about this. But reptiles like terrestrial turtles are at much higher risk.

For example, the Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) is a terrestrial turtle that lives throughout the southeastern United States in hickory-oak forests, grasslands, and river-bottom lands. These habitats offer plenty of shade and have naturally cooler temperatures so normally, these turtles aren’t at risk of overheating.

But they aren’t good climbers; Eastern Box Turtles can get caught in the sun and literally cook in their shells when they fall into holes or are unable to clamber over curbs when crossing roads.

Conclusion

The answer to the question “Can reptiles get too hot?” is “Yes, but it doesn’t happen in the normal course of events”.

Every animal has an upper body temperature limit beyond which they will die and reptiles are no exception. But reptiles that live in hot environments evolved to do so and are perfectly capable of managing their body temperatures effectively provided they are not constrained from doing so. They overheat only when their compensatory strategies are blocked or overwhelmed.

Related Now I Wonder Posts

To learn more about reptiles in general, check out these other Now I Wonder posts:

- Do reptiles have cold blood?

- Do reptiles have hearts?

- Can reptiles get too cold?

- Why can’t reptiles chew?

- Do reptiles lay eggs?

- Do reptiles give birth?

References

Behler JL, King FW. 2020. National Audubon Society Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians: North America. New York (NY): Alfred A. Knopf.

Cain ML, Bowman WD, Hacker SD. 2011. Ecology. 2nd ed. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates, Inc.

Doneley B, Monks D, Johnson R, Carmel B. 2018. Reptile Medicine and Surgery in Clinical Practice. Newark: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

Mares M. 1999. Encyclopedia of Deserts. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.