Mother Nature really surprises me sometimes.

After nearly two decades of wandering around the state of North Carolina observing, identifying, and researching the animals and plants I see, I thought I had a pretty good grasp of the state’s diversity. Rarely within the last few years have I encountered a creature so completely new to me that I’ve been unable to even hazard a guess as to what it might be.

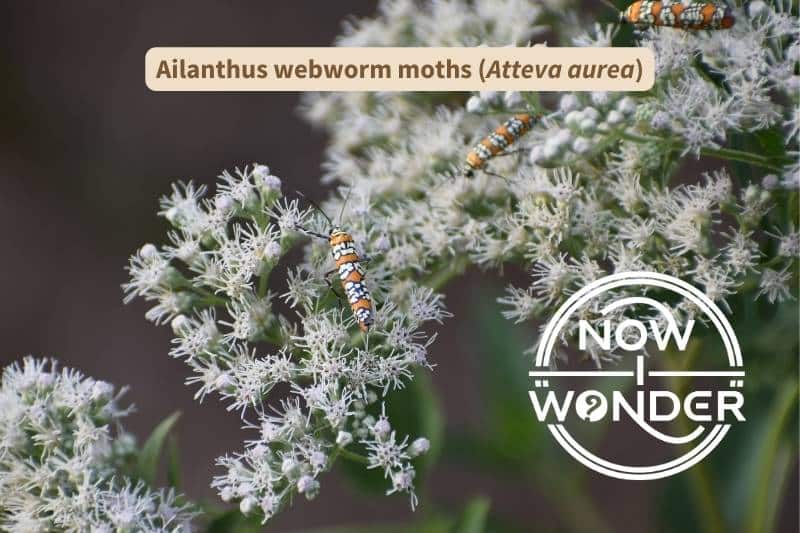

And yet, nature is astonishingly diverse, and operates on its own schedule. Many creatures can only be spotted in the wild if you are in the right place at exactly the right time. Enter my first encounter with Ailanthus Webworm moths (Atteva aurea).

I was out hiking, scanning for animals as always, and hadn’t seen much. Summer was fading into fall, temperatures were dropping, and I’d noticed a sharp drop-off in the number of creatures already. As I walked past a large stand of tall, weedy plants topped with hundreds of tiny white flowers, a tiny speck of orange caught my eye.

Peering closer, I saw a tiny shape crawling slowly over the white flowers. It was tiny and at least 15 feet away from where I was standing. All I could really see was a blur of orange. But it was moving and that’s always good enough for me. I took the best photographs I could manage and hurried home.

Thanks to my trusty telephoto lens, my camera captured the detail my eyes couldn’t see and showed me a tiny but visually striking insect. And thanks to my trusty collection of field guides, I identified it as an Ailanthus Webworm moth (Atteva aurea) – a common North Carolina insect but one that I’d never before seen.

An excellent reminder that nature always offers curious people something exciting to see!

Species Information

Classification

| Kingdom | Animalia |

| Phylum | Arthropoda |

| Class | Insecta |

| Order | Lepidoptera |

| Family | Yponomeuti- dae (the Ermine moths) |

| Genus species name | Atteva aurea |

Ailanthus Webworm moth classification has changed over the years. Many field guides refer to this species as Atteva punctella but it was renamed to Atteva aurea in 2010 based on DNA research (Wilson et al. 2015).

Butterflies and moths are sometimes categorized as “macrolepidoptera” and “microlepidoptera”. The “macro” prefix means “large” and the “micro” prefix means small. The Ailanthus Webworm moth is a “microlepidopteran” and is indeed very small, as are most species categorized in this way.

However, it is mostly coincidence that microlepidopterans are so much smaller than macrolepidopterans such as Eastern Tiger Swallowtail butterflies (Papilio glaucus). In fact, there are some “micro-” species that are nearly as large as the smallest “macro-” species.

It turns out that the distinction between the two groups is “taxonomic”, which is a way of ordering species lists based on evolutionary age. Species which evolved earlier in time are listed first, followed by those that evolved more recently (Leckie and Beadle, 2018). Microlepidopterans diverged longer ago than than the macrolepidopterans; the neat split between each group based on their relative body size is just lucky.

Physical Appearance

Eggs: I wasn’t able to find any information about Ailanthus Webworm moth eggs. I suspect that this is because they are extremely tiny, given the small size of the adults, and go unnoticed.

Caterpillars: I wasn’t able to find any information about Ailanthus Webworm moth caterpillars, although one reference I checked includes them in their “needleminer” section (Leckie and Beadle, 2018). Needleminers tunnel between the tough epidermal layers of a leaf’s surface and feed on the soft inner tissue, and often leave characteristic tracings across the leaf surface.

Adults: Adult Ailanthus Webworm moths grow to 0.4-0.6 inches (10-16 mm) long – only about as long as a grain of wild rice – and have wingspans of a little more than 1 inch (27-29 mm) (Milne and Milne, 1980). Their fore wings are bright orange and banded with four rows for black-edged whitish-yellow spots that run from side to side. Their hind wings are dark (Leckie and Beadle, 2018) but are hidden by the fore wings when not in flight.

Lifecycle

Like all lepitopterans, Ailanthus Webworm moths undergo “holometabolism”, which means they progress through four life stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Each stage is entirely distinct, with different appearances and behaviors.

In the case of moths, their larval form is called “caterpillar” and the pupal form develops in a special case called a “chrysalis”, which is unique to lepidopterans.

Habitat and Distribution

Ailanthus Webworm moths (Atteva aurea) can be found throughout North Carolina between the beginning of April to mid-November, although their density varies significantly across different regions. These moths follow their food plants; areas in which their food plants grow may sport an abundance of these moths, while other areas have hardly any at all.

Food and Feeding Behavior

Larval Host Plants

Ailanthus Webworm Moth caterpillars make communal webs on the foliage of ailanthus trees (Eaton and Kaufman, 2007). Also referred to as “tree of heaven”, Ailanthus altissima is a tree native to East Asia classified in family Simaroubaceae and is grown worldwide as an ornamental. Many consider this plant to be invasive.

Adult Host Plants

I could find no specific information about the feeding behavior or food plants of adult Ailanthus Webworm Moths.

However, the one and only time I’ve encountered these insects after years of exploring North Carolina’s wildlife was in a thick patch of flowering weeds, which I think was White Snakeroot (Eupatorium rugusum).

Each flower cluster was crawling with many moths, and since each plant had many flower clusters, there were Ailanthus Webworm Moths everywhere I looked. But the event was short-lived. When I returned to the stand after a day, I couldn’t find even a single moth.

Only the webworms themselves know if they flew off to feed somewhere else or just died off en masse. Regardless, the transition from an abundance of bright orange moths to none at all was both abrupt and extraordinary.

Fun Facts

- Despite being only about the length of a grain of wild rice, Ailanthus Webworm Moths (Atteva aurea) are actually one of the larger species of “microlepidoptera”. Most are so small as to go almost entirely unnoticed.

- The “tree-of-heaven” (Ailanthus altissima) upon which Ailanthus Webworm caterpillars feed can grow 100 feet (30 meters) high and develop trunks 3 feet (1 m) in diameter (Ailanthus, 2020).

- The first tree-of-heaven was planted in Philadelphia in 1784 and quickly spread across the eastern United States, even reaching southern Texas (Wilson et al. 2010).

References

Ailanthus 2020. Abingdon: RM Education, Ltd.

Eaton, Eric R., and Kenn Kaufman. 2007. Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America. New York, NY: Mariner Books, Harper Collins.

Leckie, Seabrooke and David Beadle. 2018. Peterson Field Guide to Moths of Southeastern North America. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

Milne, Lorus, and Margery Milne. 1980. National Audubon Society Field Guide to Insects and Spiders: North America. New York, NY: Chanticleer Press, Inc.

Wilson, John, Jean-François Landry, Daniel Janzen, Winnie Hallwachs, Vazrick Nazari, Mehrdad Hajibabaei, and Paul Hebert. 2010. “Identity of the Ailanthus Webworm Moth (Lepidoptera, Yponomeutidae), a Complex of Two Species: Evidence from DNA Barcoding, Morphology and Ecology.” ZooKeys 46: 41-60. doi:https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.46.406.