In the eat-and-be-eaten natural world, every animal is food for something else, and dragonflies are no exception. Despite being large, agile, predatory insects with the best vision in the animal world and tremendous flying ability, dragonflies are vulnerable to being caught and consumed by other, larger predators. But what animals are fast and skilled enough to catch and eat dragonflies?

Dragonflies are prey for many aquatic and terrestrial animals, including fish, frogs and toads, lizards, birds, spiders, bats, and other insects, such as robber flies, aquatic bugs and beetles, praying mantises, and other dragonflies. Predators vary depending on the dragonflies’ life stage.

None of these predators specialize in hunting dragonflies only but all can and will eat dragonflies. Read on to learn more about these important predator-prey interactions.

Overview of dragonfly predators

Dragonflies have three distinct life stages: a freshwater larval stage during which they are called “nymphs” or “naiads”, a short, transition stage when they are referred to as “tenerals”, and an adult stage during which their focus is feeding and reproduction.

Dragonflies are attacked by predators during all their life stages but are most vulnerable during their teneral phase. During this life stage, the formerly aquatic nymphs climb out of the water to complete their final transition to their adult forms. The teneral dragonflies grip vegetation, split their skins, and pull their adult bodies out.

Dragonflies are extremely vulnerable to predators during this time. It takes several hours for their wings to dry and harden enough for flight.

| Predator | Type | Example(s) | Dragonfly nymph | Teneral dragonfly | Adult dragonfly |

| Dabbling birds | Birds | Mallard duck (Anas platyrhyncos) | x | x | |

| Wading birds | Birds | Great blue heron (Ardea herodias) | x | x | |

| Insectivorous birds | Birds | Eastern phoebe (Sayornis phoebe) Great crested flycatcher (Myiarchus crinitus) Purple martin (Progne subis) Gray catbird (Dumetella carolinensis) Chimney swift (Chaetura pelagica) Barn swallow (Hirundo rustica) | x | x | |

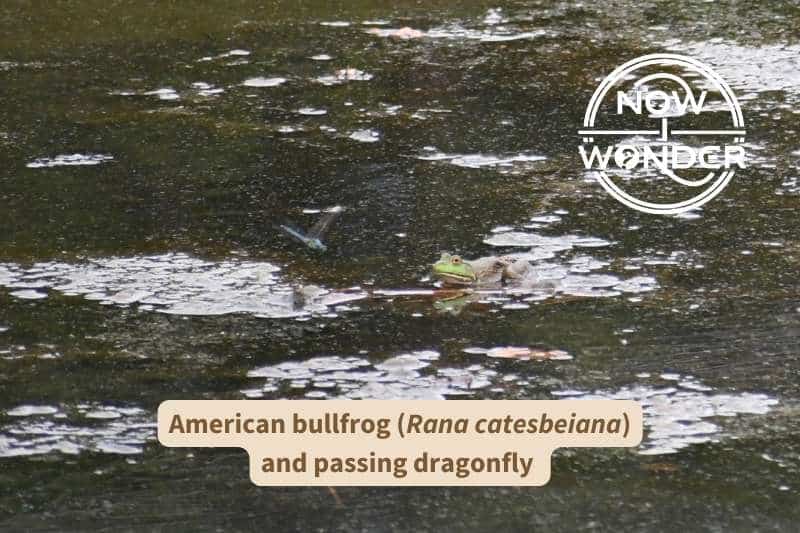

| Frogs and toads | Amphibians | American bullfrog (Rania catesbeiana) | x | x | x |

| Predaceous freshwater fishes | Fish | Common carp (Cyprinus carpio) Brown trout (Salmo trutta) Smallmouth bass (Micropterus dolomieu) Largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) | x | x | |

| Dragonflies | Insects | Dragonhunter (Hagenius brevistylus) | x | x | x |

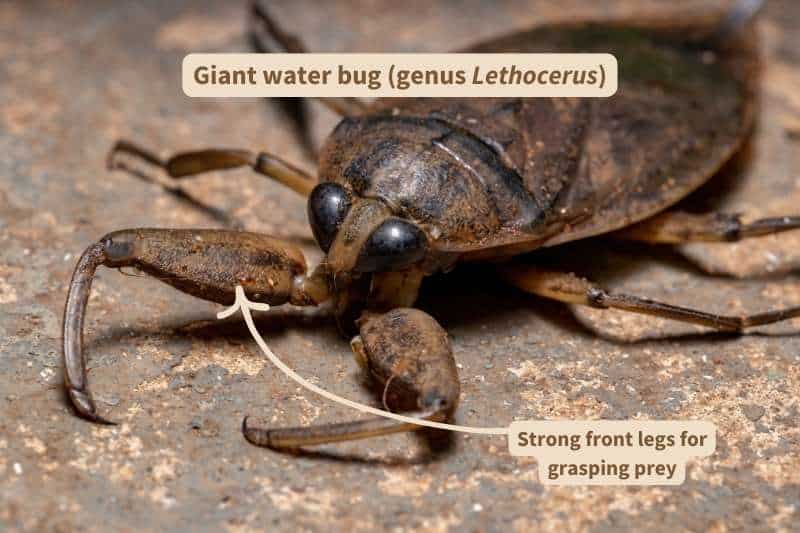

| Aquatic insects | Insects | Giant water bugs (Lethocerus sp.) Backswimmers (Notonecta sp.) Diving beetles (family Dystiscidae) | x | ||

| Robber flies | Insects | False bee killer (Promachus bastardii) | x | x | |

| Praying mantises | Insects | Carolina mantid (Stagmomantis carolina) | x | x | |

| Spiders | Arachnids | Yellow and black garden spider (Argiope aurantia) Pumpkin orb weaver spider (Araneus marmoreus) | x | ||

| Bats | Mammals | Little brown myotis (Myotis lucifugus) | |||

| Domestic cats | Mammals | Domestic short-haired cat (Felis catus) | x | x |

Birds

Birds are important dragonfly predators at every stage of a dragonfly’s life, and can be informally divided into two groups: waders and dabblers and insectivores.

Wading and dabbling birds

Dragonfly larvae are vulnerable to birds that feed on aquatic invertebrates, such as herons, ducks, and geese. Dragonfly larvae (called “nymphs” or “naiads”) are exclusively aquatic and live and develop on the substrate of freshwater ponds, lakes, streams, and rivers after hatching. Ducks and geese dabble beneath the surface and eat the creatures stirred up from the sediment.

Wading birds such as great blue herons and tricolored herons will feed on teneral and adult dragonflies, although dragonflies make up only a small portion of their diet.

Insectivorous birds

Many species of bird in several families prey on dragonflies. Some of these, found in the southeastern United States, include eastern phoebes (Sayornis phoebe), great crested flycatchers (Myiarchus crinitus), purple martins (Progne subis), and gray catbirds (Dumetella carolinensis).

These birds active chase and catch dragonflies, which is not an easy proposition. Dragonflies are some of the best fliers in the insect world, able to fly at speeds up to approximately 35 miles per hour (56 km/hr) (Abbott, 2015), fly backwards, hover effortlessly, and change direction in a millisecond. Yet many insectivorous birds are so agile in flight themselves that they pose mortal danger to every dragonfly in their vicinity.

Amphibians

Frogs and toads

Frogs prey on dragonflies of all ages because both live in and near fresh water, especially ponds, streams, marshes, and swamps.

The American bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana) is a common frog species found in the southeastern United States that eats dragonflies. During the day when dragonflies are active, these large frogs rest partially submerged and hidden in vegetation. Although they hunt mostly at night, bullfrogs will ambush passing prey when given the chance. Should a careless dragonfly fly too close to one of these waiting amphibians, the frog will lash out with its sticky tongue, snatch the dragonfly out of the air, and swallow it whole.

Toads are loosely distinguished from frogs by drier skin, shorter hind legs, and little to no webbing between their toes. They live in drier environments than frogs and dragonflies so have less opportunity to prey on dragonflies but can and do eat them when opportunity arises.

Fish

Predatory fish species found in the southeastern United States, such as common carp (Cyprinus carpio), brown trout (Salmo trutta), and both largemouth and smallmouth bass (Micropterus salmoides and Micropterus dolomieu respectively) prey on dragonflies.

Carp eat nearly anything they can find; they root around in the sediment to disturb the creatures living on and in it, which includes dragonfly nymphs. Trout feed mostly on insects other than dragonflies, but prey on nymphs when available, and are so predatory they sometimes chase flying insects and birds through the water (Alden and Nelson, 1999). Bass leap from the water to snap hovering dragonflies above the surface (Shook, 1999).

Other Insects

Other dragonflies

Dragonflies of all ages prey on their fellow dragonflies and related damselflies. Larger, more mature nymphs will feed on smaller nymphs of any species, while large adult individuals prey on smaller dragonflies.

One species notorious for preying on its fellow dragonflies is Hagenius brevistylus, otherwise known as dragonhunters. These large, clubtail dragonflies that can reach 90 mm (3.5 in) in total body length, with hind wings that can be 58 mm (2.3 in) long (Paulson, 2012).

Most dragonflies take prey smaller than themselves, but dragonhunters prey routinely on flying insects nearly as large as they are, such as butterflies, jewelwing damselflies, and other dragonflies (Paulson, 2012). The skill and enthusiasm with which they hunt their fellow dragonflies led to their common name “dragonhunter”.

Aquatic Insects

Some species of aquatic insect prey on dragonfly nymphs, including giant water bugs, backswimmers, and water beetles.

Giant water bugs are the biggest of the three and are classified in family Belostomidae). These “true bugs” (those insects classified in order Hemiptera) can grow 45-60 mm (1.75-2.4 in) long. They use their flattened hind legs to oar through the water, and their front legs to grasp and hold prey such as dragonfly larvae, then stab with their sharp, sucking beak.

Backswimmers are also classified as true bugs but are in family Notonectidae, and are named because of their habit of swimming upside down. These insects are much smaller than giant water bugs, growing to only 10 -13 mm (0.4-0.5 in), but are more than powerful enough to attack dragonfly nymphs successfully.

Water beetles are predaceous insects classified in the beetle order Coleoptera, family Dytiscidae, and can be such aggressive and powerful hunters that their common name is “water tiger”. These beetles are intermediate in size to giant water bugs and backswimmers, depending on the species. In general, they reach sizes between 1.5-40 mm (0.0625-1.625 in); the southeastern United States is home to a species on the larger side, aptly named “large diving beetle” (genus Dytiscus).

Robber flies

Robber flies are a type of fly classified in order Diptera, family Asilidae, and kill their prey by stabbing them to death with their sharp mouth spikes, or “proboscises”; they cannot sting.

These opportunistic predators are very strong fliers that attack flying insects. They are perch predators; they perch, wait for prey such as dragonflies to fly too near, then fly out to intercept. Robber flies grab prey with their legs, stab them with their long, sharp proboscises, and inject them with paralyzing saliva. The saliva also liquefies the preys’ inner tissues, allowing the flies to suck them dry.

These insects are such powerful predators that they regularly attack large, dangerous insects such as dragonflies, and even arachnids like spiders.

For more information about robber flies, check out this other Now I Wonder post “Do insects ever eat spiders? Part 2 Attacks from the Air“.

Praying Mantises

Praying mantises are powerful predatory insects capable of attacking dragonflies, although they do not specialize on them as prey.

Mantises are classified in order Mantodea, and are true ambush predators; they rely on their magnificent camouflage to blend into vegetation and on their excellent vision to spot prey and gauge attack distance.

A mantid attacks by snapping its sharply spined forelegs forward at lightning speed to impale its prey. The movement happens so fast that an unwary dragonfly who ventures too close to a lurking mantid will likely be dead before it can even register the attack.

Arachnids

Orb-web weaving spiders

Spiders are famous for constructing the most perfect passive insect traps the world has ever known – spider webs. Perfected over millions of years of evolution, spider webs capture and restrain a wide variety of flying insects long enough for the resident arachnids to kill and consume them.

Dragonflies get caught in large, vertical spider webs constructed by orb web weaving spiders of family Araneidae. Dragonflies who collide with orb webs adhere to the sticky silk; struggles to escape worsens their entanglement. Eventually, they are killed and consumed by the resident spiders.

Orb weaver spiders range in size from tiny to some of the largest spiders found in the southeastern United States. Three large examples of species that spin webs capable of capturing dragonflies are pumpkin spiders (Araneus marmoreus), banded garden spiders (Argiope trifasciata), and yellow and black garden spiders (Argiope aurantia). Both pumpkin spiders and the garden spiders suspend their webs in vegetation and often live near water – areas through which dragonflies are likely to fly.

Orb-weavers are usually generalist predators that prey on whatever insects get caught in their web. They don’t target dragonflies specifically; their webs are passive traps that catch and hold at random. Bees and wasps (order Hymenoptera), grasshoppers (order Orthoptera), beetles (order Coleoptera), and butterflies and moths (order Lepidoptera) make up the majority of Argiope prey (Carrel and Deyrup, 2019). However, dragonflies provide orb weaver spiders a great deal of nutrition when consumed, thanks to their large size.

Mammals

Bats

Bats are extremely efficient predators of flying insects, including dragonflies. They locate prey by sending out ultrasonic squeaks that bounce off the bodies of prey. The bats listen for the return signals and use the information to intercept insects in flight.

However, bats are nocturnal and dragonflies are diurnal and active during the day; overlap between the two animals’ active periods occurs only at certain times of day.

Around dusk, bats leave their roosts around dusk to feed on flying insects through the night; dragonflies seek shelter in vegetation or in tree canopies, where they will spend the night hiding from predators. The primary window for bats to attack dragonflies is during this dusk transition period, when hungry bats emerge to hunt and dragonflies are still in flight.

The situation reverses around dawn. Bats leave off feeding and fly back to their roosts, where they will rest and hide for the day, while dragonflies begin to stir. Bats can also feed on dragonflies during this time, but do so less for a few reasons. First, the bats will have spent all night feeding on moths so will not be as hungry or motivated to hunt. Second, dragonflies are ectothermic creatures, which means they rely on the sun and ambient temperatures to get warm enough to fly. so may emerge after the bats have already retreated to their roosts.

That said, blue dasher dragonflies (Pachydiplax longipennis) will hunt moths at night around street lights (Paulson, 2012), which puts them in the same vicinity as hunting bats.

Domestic Cats

Domestic cats (Felis catus) can be superb hunters of many wild creatures, including dragonflies. Since dragonflies can fly, and cats clearly can’t, domestic cats prey mostly on dragonflies found on the ground or within a few feet from the ground. This can include dragonflies the cats catch basking in the sun or those that fly or hover too close to the prowling felid.

Cats hunt by slinking slowly and unobtrusively closer to prey then launching a fast attack. They have fast reflexes, excellent balance, and five retractable claws on each front paw that snag and hold prey. Dragonflies can see nearly 360 degrees around them; they see less well immediately behind and below them. Cats that sneak up from behind can often get close enough to swat dragonflies.

Conclusion

Dragonflies are impressive insects in many ways, including their flying ability, their acute vision, and their sheer size. But they also represent tidy little packages of protein and nutrients for any creature fast enough and powerful enough to eat them. And the law of nature being what it is, many animals evolved those abilities and make fabulous meals out of dragonflies.

Related Now I Wonder Posts

For more about dragonflies and other insects in order Odonata, check out these other Now I Wonder posts:

- Is a dragonfly a fly?

- Can dragonflies walk?

- What do dragonflies do at night?

- What is the difference between a dragonfly and a damselfly?

- Dragonflies vs. Butterflies Part 1: First Comes Form

- Dragonflies vs. Butterflies Part 2: Second Comes Function

- Are there different types of dragonflies?

- Dragonflies vs. Horse Flies: Allies vs. Enemies

- What is the difference between dragonflies and mayflies?

- Dragonflies vs. Mosquito Hawks: What’s the difference?

- Dragonflies vs. Fireflies: What are the differences?

- Dragonflies vs. The Ultimate Insect Trap: Spider Webs

- Meet North Carolina’s Biggest Dragonflies

References

Abbott, John C.. Dragonflies of Texas : A Field Guide, University of Texas Press, 2015.

Alden, Peter, Nelson, Gil. 1999. National Audubon Society Field Guide to the Southeastern United States. New York, N.Y.: Alfred A. Knopf.

Carrel, James E., and Deyrup, Mark. 2019. “Analysis of Body Size, Web Size, and Diet of Two Congeneric Orb-Weaving Spiders (Araneae: Araneidae) Syntopic in Florida Scrub.” The Florida Entomologist 102 (2) (06): 388-394. https://doi.org/10.1653/024.102.0215

Paulson, Dennis. 2012. Dragonflies and Damselflies of the East. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Shook, Michael D. 1999. The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Fly Fishing. New York, N.Y.: Penguin Group [USA], Inc.