A blazing orange and black butterfly, large wingspan, toxic to predators. No, it’s not the Monarch butterfly, it’s the Gulf Fritillary.

A summer migrant to North Carolina, a casual nature observer is more likely to spot a Gulf Fritillary butterfly (Agraulis vanillae) than a Monarch (Danaus plexippus) while wandering the state. But chances are good that the observer will mistake the Gulf Fritillary for a Monarch- Monarch butterflies are by far the most famous large, orange and black butterfly and get all the attention.

But learning to recognize Gulf Fritillary butterflies- and learning about them- is worth your time. They are flashy, fun to watch, and often as easy to find as just stepping out your own front door.

Fun Facts About Gulf Fritillary Butterflies To Wow Your Friends

- Adult Gulf Fritillary butterflies (Agraulis vanillae) release a pungent liquid from special glands in their abdomens when threatened (Ross et al. 2001). This liquid is so odoriferous even humans can apparently smell it (which is really saying something, given our feeble sense of smell).

- In females, the glands are located between abdominal sections 7 and 8; in males, they are located within the claspers at their abdominal tips (Ross et al. 2001).

- Normally, the bright yellow glands are hidden from view but both sexes evert them when under stress (Ross et al. 2001).

- This noxious fluid appears to be a remarkably effective anti-predator defense.

- In one case, 50–70 Gulf Fritillary butterflies were released every week into the “Butterflies in Flight” exhibit at the Audubon Zoological Garden, New Orleans, Louisiana to re-populate the conservatory. Also in the exhibit were approximately 60-70 free-flying insectivorous birds that are normally aggressive predators of butterflies. Despite being monitored almost daily for nine months for approximately 60 hours, volunteers and staff could find no evidence of attacks on Gulf Fritillaries (Ross et al. 2001).

- In another case, Gulf Fritillary butterflies were the most abundant butterflies species present in an open-air butterfly garden by a factor of 10. A large variety of butterfly predators also lived in the garden, including spiders, assassin bugs, dragonflies, wasps, ambush bugs, praying mantids, green anole lizards, and insectivorous birds. These predators apparently ignored the Gulf Fritillaries; not one attack on a Gulf Fritillary was ever observed, either directly or indirectly (i.e. detached wings on the ground) (Ross et al. 2001).

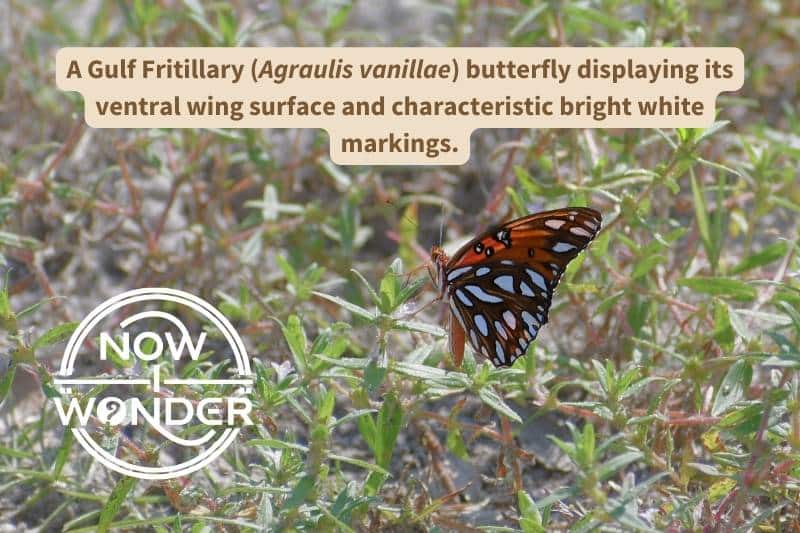

- Gulf Fritillary butterflies (Agraulis vanillae) are sometimes known as “espejitos” (“little mirrors”) in Spanish, thanks to the large, reflective white spots that decorate the underside of their wings (Dolinko et al. 2021).

How Are Gulf Fritillary Butterflies Classified?

| Kingdom | Animalia |

| Phylum | Arthropoda |

| Class | Insecta |

| Order | Lepidoptera |

| Family | Nymphalidae (“brush-foot butterflies”, sub-family Heliconiiae, “longwing butterflies” |

| Genus species | Agraulis vanillae |

How Do I Know I’m Looking at a Gulf Fritillary Butterfly?

Appearance of Gulf Fritillary Butterfly Eggs

Gulf Fritillary (Agraulis vanillae) eggs are light yellow, ridged, spindle-shaped, and about 0.039 inches (1mm) long. The female butterfly lays her eggs singly on the leaves and stems of plants in the Passiflora family.

Appearance of Gulf Fritillary Butterfly Caterpillars / Larvae

Gulf Fritillary (Agraulis vanillae) larvae hatch from their eggs in about three days (Pena et al. 2002) and are only 0.1 inches (3mm) long. As the caterpillars grow through their five instars (stages of growth between molts), they increase in size to 1.4-1.6inches (35-40mm) in length.

Gulf Fritillary caterpillars are glossy and striped either red or orange and black. Their heads are orange above and black below, with two branched black spines that curve backwards. Their thoracic legs (true legs) are black and their bodies are spiked with rows of branched, black spines.

Their chrysalids are very well-camouflaged as dried leaves and are about 1 inch (25mm) long.

Appearance of Adult Gulf Fritillary Butterflies

Gulf Fritillary (Agraulis vanillae) butterflies have wingspans of about 3.0 inches (7.6cm) and both wing surfaces are both brightly colored and distinctive.

The upper wing surface (or “dorsal” surface) is bright orange with black markings. Gulf Fritillaries have two distinctive field marks on their upper wings that will help you identify them.

The first is three white wing spots, rimmed in black, located about a third of the way along the leading edge of each forewing.

The second is a band of black markings that enclose the bright orange wing color along the margin of the hind wings, making a chain of orange spots.

The under wing surface (or “ventral” surface) is even more distinctive. The underside is covered in large silvery spots that actually gleam metallic at nearly all angles of light. It’s likely that Gulf Fritillaries can get away with this eye-catching visual display only because their body tissues are toxic to many predators.

While their wings get most of the attention, Gulf Fritillary butterflies have colorful bodies and eyes as well. Their furry bodies that are bright orange above and white below and their eyes are orange and white striped.

When Can I Find Gulf Fritillary Butterflies in North Carolina?

Gulf Fritillary (Agraulis vanillae) butterflies have a typical lepidopteran lifecycle, which involves the usual four life stages characteristic of all insects- egg, larva (known as “caterpillar”), pupa, and adult.

Gulf Fritillary caterpillars hatch from their eggs in about three days. They are tiny at first but grow rapidly through five instars (growth stages separated by skin molts).

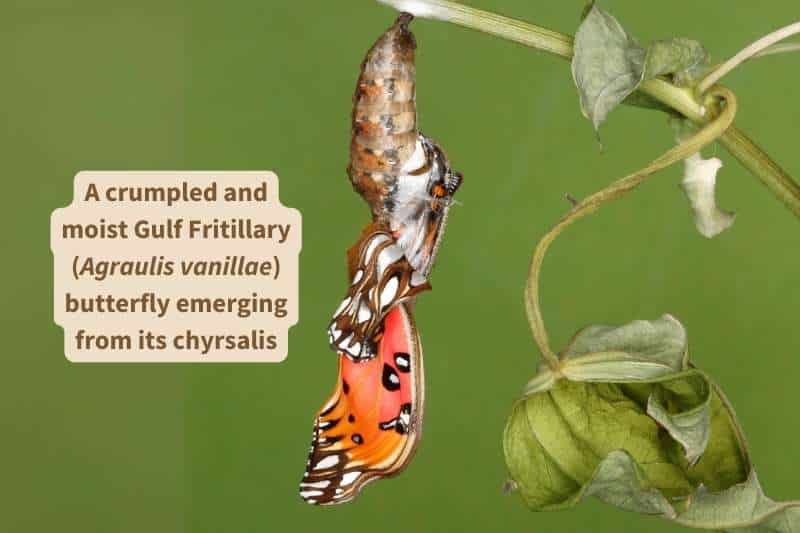

After about 17 days, the caterpillars are ready to pupate. Their outer skin forms a “puparium”- better known as a “chrysalis”. Chrysalids are weather-tight, protective cases within which the pupae’s bodies transform into winged adult butterflies in a process called “complete metamorphosis”. Gulf Fritillaries metamorphose in about seven days; then the adult butterflies emerge, dry and stiffen their wings, and fly off to feed and mate.

In North Carolina, Gulf Fritillary (Agraulis vanillae) butterflies have one to two flights per warm season, from early spring through fall. They start to appear in May, then become increasingly abundant and widespread throughout the summer and peak in September and October.

Where Should I Look to Find Gulf Fritillary Butterflies in North Carolina?

Gulf Fritillary (Agraulis vanillae) butterflies are easy to entice into your North Carolina garden. They may already be present since they are so common during the late summer months, but encouraging them to visit is as easy as planting some passion vines in your garden.

Beyond the garden, these butterflies are likely to be found anywhere with abundant flowers, especially open woodlands, meadows, brushy fields, utility cuts, and along roadways.

Your best bet to spot Gulf Fritillary butterflies in the wild is to locate some purple passion flower plants (Passiflora incarnata).

P. incarnata is a native North Carolina perennial vine that grows wild along roadsides and fencerows. Also called “maypops” because their small, melon-shaped fruits “pop” when squeezed, the distinctive fringed purple wildflowers bloom from May through July. Purple passion flower plants are unmistakable when in flower and Gulf Fritillary butterflies are almost guaranteed to be flitting around in the vicinity.

What Do Gulf Fritillary Butterflies Eat

Gulf Fritillary Butterfly Larval Food Plants

Gulf Fritillary (Agraulis vanillae) caterpillars eat plants in the passion vine (or passion flower) family Passifloraceae. This family includes native southeastern plants like corky-stemmed passion vine and maypop (Passiflora incarnata, also called purple passion flower).

This species is a specialist feeder- they rely on passion flower plants and can’t survive on anything else. Luckily, passion flowers are cultivated and sold as ornamental plants. Gulf Fritillaries feed readily on these cultivated Passiflora plants, so have actually expanded their range west over the last hundred years as people plant them in their gardens and landscaping (Halsch et al. 2019).

Adult Gulf Fritillary Butterfly Food

Adult Gulf Fritillary butterflies (Agraulis vanillae) eat nectar and visit a variety of flowers throughout the flight season. But since their caterpillars are dependent on passion flower vines (Passiflora sp.), they stick close to these plants and feed on flowers that grow within flight distance.

References

Dolinko Andrés, Luisa Borgmann, Christian Lutz, Ernest Ronald Curticean, Irene Wacker, Vidal María Sol, Szischik Candela, et al. 2021. “Analysis of the Optical Properties of the Silvery Spots on the Wings of the Gulf Fritillary, Dione Vanillae.” Scientific Reports (Nature Publisher Group) 11 (1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-98237-9.

Halsch, Christopher A., Matthew Forister, Arthur M. Shapiro, James H. Thorne, and Dave P. Waetjen. 2019. A Winner in the Anthropocene: Changing Host Plant Distribution Explains Geographic Range Expansion in the Gulf Fritillary Butterfly. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1101/754010.

Pena, J., Sharp, J., and Wysoki, M.. 2002. Tropical Fruit Pests and Pollinators : Biology, Economic Importance, Natural Enemies and Control. Wallingford: CABI.

Rodríguez-Dimaté, Francisco Andrés, Jú Poderoso, Rafael Coelho Ribeiro, Bruno Pandelo Brügger, Carlos Frederico Wilcken, José Eduardo Serrão, and José Cola Zanuncio. 2016. “Palmistichus Elaeisis (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) Parasitizing Pupae of the Passion Fruit Pest Agraulis Vanillae Vanillae (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae).” The Florida Entomologist 99 (1) (03): 130-132.

Ross, Gary N., Henry M. Fales, Helen A. Lloyd, Tappey Jones, Edward A. Sokoloski, Kimberly Marshall-batty, and Murray S. Blum. 2001. “Novel Chemistry of Abdominal Defensive Glands of Nymphalid Butterfly Agraulis Vanillae.” Journal of Chemical Ecology 27 (6) (06): 1219-28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010372114144.